This piece will be further developed and enriched with new visual material and other information. Please be sure to subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates.

“Just as a child absorbs the world like a sponge, I learn from the earth of my hometown.”

Those are the words of Sokei Aoyama, a master potter in Onada, Tajimi and self-described experimental archaeologist. Indeed, the ground in Onada has been hiding traces of an exciting past in Japanese pottery, traces that has come to light in recent years. Shining brightest in this story is the Shiro Tenmoku, the traditional Japanese white tenmoku teacups. Tenmoku have been described as “tea bowls with a distinctive shape that flares upward from the base and then narrows almost to a vertical at the rim; an unglazed lower section; and a rather short foot.” (See note 01). When Aoyama-sensei starts to speak about this subject, it’s hard not to be smitten by his enthusiasm. We spent several hot summer afternoons in his workshop listening to his story, drinking green tea by the fan. It is a story where the old kilns of Onada come to life once more, and the beautiful white teacups they produced. Had I only known the value of the Shiro Tenmoku reproductions Aoyama-sensei served our tea in, my handling of the items would have been a rather nerve-wrecking affair.

It must have been arduous work for pottery workers in those days, firing their wares for days. Hot summer days like this must have taken their toll. They turned the rare, white clay in Onada into teacups for the upper class - warlords and samurai yearning for the temporary quiet of the tea ceremony in between political intrigue and bouts on the battlefield. There were also a growing number of wealthy tea aficionados in the merchant class.

Those are the words of Sokei Aoyama, a master potter in Onada, Tajimi and self-described experimental archaeologist. Indeed, the ground in Onada has been hiding traces of an exciting past in Japanese pottery, traces that has come to light in recent years. Shining brightest in this story is the Shiro Tenmoku, the traditional Japanese white tenmoku teacups. Tenmoku have been described as “tea bowls with a distinctive shape that flares upward from the base and then narrows almost to a vertical at the rim; an unglazed lower section; and a rather short foot.” (See note 01). When Aoyama-sensei starts to speak about this subject, it’s hard not to be smitten by his enthusiasm. We spent several hot summer afternoons in his workshop listening to his story, drinking green tea by the fan. It is a story where the old kilns of Onada come to life once more, and the beautiful white teacups they produced. Had I only known the value of the Shiro Tenmoku reproductions Aoyama-sensei served our tea in, my handling of the items would have been a rather nerve-wrecking affair.

It must have been arduous work for pottery workers in those days, firing their wares for days. Hot summer days like this must have taken their toll. They turned the rare, white clay in Onada into teacups for the upper class - warlords and samurai yearning for the temporary quiet of the tea ceremony in between political intrigue and bouts on the battlefield. There were also a growing number of wealthy tea aficionados in the merchant class.

Onada is located in Tajimi city, Gifu, Japan. Is is part of the historic Mino region, famous for Mino ware such as Shino and Oribe.

an old misconception

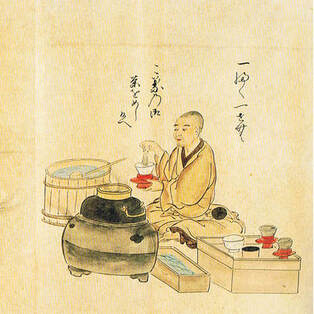

There is a wonderful, remarkably vivid picture depicting every day's life (月次風俗図) in the Muromachi period (approximately 1336 to 1573). It is included in a book titled "The Tea Ceremony Picture Collection" (茶の湯絵画資料集成) published by Heibonsha. In the picture we see a busy city scene, full of people, and they all seem to be still alive even today. Two young boys are fighting, pulling each others hair. A man in a pointed hat, sword dangling from his side, is running towards them. A guard, trying to stop them? A pretty lady in a fine dress carries a small drum. She is smiling at someone. And there is a peddler of teas made from herbal extracts (senjimono-uri ja:煎じ物売), his gear dangling from both ends of a yoke across his shoulder. In busy places like this, in front of the gates to a shrine or temple, you would also find open tea houses. The Tea Ceremony company Bokushinan (卜深庵) describes tea houses in Kyoto of that day on its web site:

In the Muromachi period improving goods distribution contributed to the spread of tea drinking among the common people. Ippuku Issen tea sellers start to appear at the gates of Shinto shrines like the Kitane Tenmangu, Kamo Ryosha, Gionsha, and buddhist temples like the Kiyomizudera and Mibudera. The shops were in other words trading to a wide spectrum of religious believers.

People drank tea not only to quench their thirst or for relaxation, but also for the medical and cleansing effects the drink was believed to have. The tea house also served as a symbolic portal between everyday’s life and the sacred place beyond the gate.

We find such an open tea house in another picture (2). A monk is preparing a cup of macha in a white cup, which looks remarkably similar to a Shiro Tenmoku in shape and colour, as well as the design of the stand, which he holds in his left hand, cup on top. This trade came to be called Ippuku Issen (一服一銭) because one portion of tea (ippuku) was priced at one sen.

Shiro Tenmoku teacups were until recent years believed to be early forms of the later Momoyama era Shino ware. Now we have reason to believe differently.

In the 1930s, Tajimi born Toyozō Arakawa (1894 - 1985), a famous potter in the Shino ware tradition, set out on a search for the origin of the Momoyama era style of Shino pottery. He discovered that Shino had its roots in Kani, close to Tajimi, and set out to recreate the pottery. He re-engineered forgotten techniques to create this beautiful pottery, characterised by its thick white feldspar glazes. Today, Shino is widespread in pottery studios both in Japan and abroad. Arakawa, a giant among pottery experts in Japan, has left his mark in the story of Mino ware.

It is understandable that the Japanese treasure pottery originating in this country. Since ancient times, China has had an enormous influence on Japanese pottery culture, and there are a few cases where one can say the origin of a form was Japanese. It is quite notable that many of the pottery works listed as National Treasures by the Japanese government were imported from China. Most of those Chinese items are tenmoku tea bowls. Chinese technology was ancient and extremely sophisticated. One could argue that the Japanese caught up with the potters on the Asian mainland, even falling further behind, isolated on their island. One could also argue that they set out on their own path, away from perfect symmetry and towards something very different. We will return to this later.

Shino-ware was until recently regarded as the only form of white pottery that can genuinely be said to have originated in Japan. Arakawa may have been biased when he concludes that two the oldest Shiro Tenmoku of Japanese origin that had been discovered so far must be Shino in his book "Shino, Kiseto, Setuguro" in 1989 (4):

Without doubt, Shino ware is the style of pottery most representative of Japan. The discovery of white, choseki [長石: Feldspar] glazed wares has a great significance for how we view the history of pottery in Japan.

The two extremely rare Japanese Shiro Tenmoku cups are in focus for this discussion. One is known to have been in possession by the daimyo (lord) Owari Tokugawa, and the other by the daimyo house of Maeda. These two are the oldest and most famous pieces of their kind. Arakawa argued that they are centrepieces in the history of Shino ware.

Shiro Tenmoku is the oldest form of Shino ware. The legendary two cups said to have once been in Joo’s possession have the appearance of Kiseto ware. I have no doubt they are Shino. They are feldspar glazed Shino, fired at very high temperature and 'naked' [without protective fire clay]. These two cups are the oldest in existence today. Some speculate they are products from the Jourinji kiln or the Gotomaki kiln [in Toki].

Arakawa illustrates with a photograph of the Owari Tokugawa owned Shiro Tenmoku, and one discovered some years before his writing at the Kamashita kiln. He dates both to the second half of the 16th century. If they were indeed Shino they would be the start of the form of pottery Arakawa regarded to be most representative of Japanese culture. He seems to be quite certain:

Nobody can be sure if these two cups were produced in Seto or Mino. What can be said is that they are not Kiseto ware, because they are feldspar glazed. Admittedly, their glazing do contain some ash, but the Tokugawa one in particular show signs of having been fired unprotected by fire clay (saya) (5). [...] It must have been a small kiln with little loading capacity, so the cup had to be placed near the fire. Ash containing iron fell on it. This resulted in a green bidoro (6) glaze, and an appearance quite similar to Kiseto ware. This is quite common when Shino is fired at too high temperature.

Aoyama-sensei was unconvinced. “Arakawa-sensei thought the cups looked a bit odd, but that they must have been fired too long, too close to the fire, and sprinkled by ash, explaining the ash content in the glazing” he says. Ash glazing is typical for Shiro Tenmoku, while choseki (feldspar) glazing is typical for Shino ware. “Even if the firing happened this way," Aoyama-sensei stresses, "the transparency of the glazing wouldn’t have been there.”

Arakawa notes other oddities about the two ancient Shiro Tenmoku, but again finds an explanation:

Arakawa notes other oddities about the two ancient Shiro Tenmoku, but again finds an explanation:

[...]The objects are dotted with tiny, black spots. This is because of the high temperature firing, where sand-like dust particles swirled around inside the kiln, falling onto the cups, sticking to their surface.

Three white Japanese tea cups from this early period are stored by the Tokugawa Art Museum in Nagoya, Fujita Art Museum, and the Kosetsu Art Museum in Kobe. These Shiro Tenmoku cups (shiro is the Japanese word for white) are listed as Important National Treasures by the Japanese government. Two are the Japanese ones we are discussing, one is Korean.

The cups embodies the heart and spirit of rustic simplicity in tea that Japan has become famous for - the wabicha (wabi tea ceremony). Wabi-sabi has to do with the acceptance of transience and imperfection. Taking a close look, you will see that the shapes of these cups are not perfect, but slightly crooked. This contrasts with Chinese tradition, once viewed as the aesthetic ideal by the tea drinking nobility in Japan. The Chinese valued symmetry, in Japan, crooked lines became the ideal.

If Arakawa was correct and these white cups were indeed Shino, it would mean that they were created in the Azuchi–Momoyama period, which spans the years from 1573 to 1603. Many view this era as a golden age of Japanese culture and art. But there are historical records of a much earlier appearance of these Japanese white tea cups. How can this be? The mystery deepens. It is one in which Aoyama-sensei's home village Onada plays a central role.

The origins of Shiro tenmoku

For copyright reasons we can't display the museum owned Shiro Tenmoku cups. Below is a link to the cup once owned by lord Tokugawa, discussed in this article. It was excavated in Aichi Prefecture and dated to the Muromachi period (1338 - 1573). Aichi borders to Gifu prefecture, where Onada is situated.

Height: 66mm

Width of mouth: 121mm

Width of foot: 45mm

Description: The substrate is a rough soil with a pale eggshell color, exposed below the waist. Thick, semipermeable white glaze. There is rough intrusion throughout. There is "stickiness" where the glaze flowed down and gathered at two places on the ouside.

Height: 66mm

Width of mouth: 121mm

Width of foot: 45mm

Description: The substrate is a rough soil with a pale eggshell color, exposed below the waist. Thick, semipermeable white glaze. There is rough intrusion throughout. There is "stickiness" where the glaze flowed down and gathered at two places on the ouside.

When and where was this white pottery invented? The Japanese tea master Takeno Jōō (武野 紹鴎, 1502-1555) speaks of a white teacup in his writings. He lived in a transitional period of Japan’s cultural history when practitioners of the tea ceremony shifted from Chinese to Korean, and then Japanese objects and the arts of wabicha begin to emerge. A wealthy merchant in Sakai with access to exclusive tea utensils, Takeno Jōō became a strong proponent for wabicha. Some believe his white cup must have been of Chinese origin, possibly a haikatsugi tenmoku, which have a two-layered glaze. Others hold that it must have been Japanese. Aoyama-sensei is one of them.

“There are many kinds of tenmoku in China, but white varieties are scarce,” he explains. “To my knowledge what white tenmoku there are, are the products of some manufacturing mistake. Many today believe the cup mentioned by Takeno Jōō was a white tenmoku produced in Japan. Supporters of this theory include the Tokugawa Art Museum and Fujita Art Museum, as well as the Kosetsu Art Museum in Kobe.”

Aoyama-sensei has made it his lifework not only to prove that shiro tenmoku is Japanese, but that it also is not Shino but something entirely different. Findings made in excavations at Onada (see Google maps for location) seemed to tell a new story. Based on these discoveries he has spent decades recreating shiro tenmoku from local clay, employing the techniques of those times. The similarities with the two museum owned pieces are striking.

“There are many kinds of tenmoku in China, but white varieties are scarce,” he explains. “To my knowledge what white tenmoku there are, are the products of some manufacturing mistake. Many today believe the cup mentioned by Takeno Jōō was a white tenmoku produced in Japan. Supporters of this theory include the Tokugawa Art Museum and Fujita Art Museum, as well as the Kosetsu Art Museum in Kobe.”

Aoyama-sensei has made it his lifework not only to prove that shiro tenmoku is Japanese, but that it also is not Shino but something entirely different. Findings made in excavations at Onada (see Google maps for location) seemed to tell a new story. Based on these discoveries he has spent decades recreating shiro tenmoku from local clay, employing the techniques of those times. The similarities with the two museum owned pieces are striking.

The discovery in Onada

The first tenmoku tea cups used in Japan were imports from China - the so-called karamono. Native production in Japan began in the 13th century in Seto, a neighbouring region to Mino. In Tajimi, a Mino city, the history of pottery goes back to the 7th century. Several of the Tajimi kilns were located in Onada, taking advantage of its rare clay resources. "In a time when there were no efficient transportation infrastructure in place, proximity to good clay was the primary concern when establishing a kiln," Aoyama-sensei explains. By the 15th-century tenmoku production had begun in Mino. The first tenmoku made here were produced in koseto-type kilns.

Two types of glazings were used, one containing feldspar (choseki gusuri) which resulted in cups darkish in colour, and one based on ash (haigusuri) which resulted in whitish cups. Excavations have revealed that the Oroshi Nishiyama kiln and other kilns in the Mino region produced these types of pottery. By the 16th-century tenmoku production had commenced in Onada. The Onada Kamashita and Onada Hakusan kilns used both iron based glazing and ash glazing, the latter resulting in the white tea cups we shall call shiro tenmoku (white tenmoku) in this article.

Two types of glazings were used, one containing feldspar (choseki gusuri) which resulted in cups darkish in colour, and one based on ash (haigusuri) which resulted in whitish cups. Excavations have revealed that the Oroshi Nishiyama kiln and other kilns in the Mino region produced these types of pottery. By the 16th-century tenmoku production had commenced in Onada. The Onada Kamashita and Onada Hakusan kilns used both iron based glazing and ash glazing, the latter resulting in the white tea cups we shall call shiro tenmoku (white tenmoku) in this article.

In 1994 there was an urgent excavation in Onada because road construction works threatened to destroy areas where the ancient kilns had stood. Large numbers of pieces of shiro tenmoku were discovered at the Onada Kamashita kiln No. 6. There was immediate speculation that they might be related to the two Japanese Shiro Tenmoku cups listed as Important National Treasures by the government. Could it be that they had been produced in Onada?

Two camps were disputing this matter. One held that the ancient shiro tenmoku had been produced with feldspar based glazing. The opposing camp maintained that the glazing was instead ash-based. Was it possible to trace the origins of the museum owned cups by studying the glazings? Was there a reliable method in the first place? Aoyama-sensei was convinced that the cups must be of Onada origin and began working to re-engineer the production method of the shiro tenmoku, collaborating with scholars to produce both practical and academic evidence to prove his case.

Two camps were disputing this matter. One held that the ancient shiro tenmoku had been produced with feldspar based glazing. The opposing camp maintained that the glazing was instead ash-based. Was it possible to trace the origins of the museum owned cups by studying the glazings? Was there a reliable method in the first place? Aoyama-sensei was convinced that the cups must be of Onada origin and began working to re-engineer the production method of the shiro tenmoku, collaborating with scholars to produce both practical and academic evidence to prove his case.

The characteristics of Shiro Tenmoku

“The most important factor influencing the look of a piece of pottery is the ceramic material used,” says Aoyama-sensei. "The clay strongly influences colour, the overall look and the properties of the pottery determining its usability as utensils. Proximity to good clay was critical to efficient production. In the neighbouring village Takata, for example, the clay is especially suitable for making sake jars (tokkuri), because jars made from this clay can hold liquid for long periods of time without leaking. Aoyama-sensei suspected that there were areas in Onada with clay perfect for the creation of Shiro Tenmoku, and began to search for their location. This clay is essential because of the way it influences the glazing when fired.

The analysis of the ceramic material in the shirotenmoku discovered at the Onada Kamashita Koyoshigun kiln No. 6 concluded that compared to the ceramic material typically used in Shino it was higher in Felsite (10.77 compared to 6.55), had a much larger clay component (48.52 compared to 31.37), and contained much less Quartzite (40.71 compared to 61.07) (7). But this was not the only property that distinguished it from Shino.

“In the excavation of the grounds at the ruins of Kamashita kiln five white cups were discovered, four from kiln No. 6 and one from kiln No. 1," Aoyama-sensei explains. "One was genuinely white and the others orange or brownish. After analysis it was concluded that they were related to true Shiro Tenmoku, but not quite of the same family. There is an easy way to identify the real thing. You need to look for “cat whiskers cracks” in the glazing.” He rummages around in his workshop for a while and finds an ancient looking piece of broken pottery.

The analysis of the ceramic material in the shirotenmoku discovered at the Onada Kamashita Koyoshigun kiln No. 6 concluded that compared to the ceramic material typically used in Shino it was higher in Felsite (10.77 compared to 6.55), had a much larger clay component (48.52 compared to 31.37), and contained much less Quartzite (40.71 compared to 61.07) (7). But this was not the only property that distinguished it from Shino.

“In the excavation of the grounds at the ruins of Kamashita kiln five white cups were discovered, four from kiln No. 6 and one from kiln No. 1," Aoyama-sensei explains. "One was genuinely white and the others orange or brownish. After analysis it was concluded that they were related to true Shiro Tenmoku, but not quite of the same family. There is an easy way to identify the real thing. You need to look for “cat whiskers cracks” in the glazing.” He rummages around in his workshop for a while and finds an ancient looking piece of broken pottery.

“Take a look at these cracks,” he says. “This is a piece produced in Onada. The cracks are a unique feature. Only clay from Onada affects the glazing this way. Now, let’s compare to a piece of Shino ware. You remember Arakawa-sensei thought Shiro Tenmoku was Shino ware?”

“When I first saw an original Shiro Tenmoku teacup at the Showa Art Museum in Nagoya in 1979, Aoyama-sensei continues, "I didn’t think it looked like Shino at all, in spite of Arakawa’s conclusions. I had long had suspicions that Shiro Tenmoku must have originated in Onada - even produced here exclusively. I talked to various knowledgeable people about it. There had been some findings of teacups in the area, but it couldn’t be determined that they were related to the Shiro Tenmoku in the museums."

"I saw signs of a connection. To begin with, there are these unique cracks or lines in the glazing of Onada pottery that are also visible on the cups in the museums. Previously the consensus was that too long firing must have caused them, but we now know they appear because of the way the ash glaze penetrates the ceramic material during the firing. It's a phenomenon particular to the interplay between the ash glaze and a particular kind if clay. That clay only exists here in Onada.”

Ash glazes are ceramic glazes made from the ash of various kinds of wood or straw. The glaze has glasslike and pooling (buildup of glaze) characteristics which put emphasis on the surface texture of the piece being glazed. Wood ash glazes result in mostly dark brown to green colours. The Onada potters used a Kiseto variant of glaze that interacted with the clay chemically, resulting in a white finish. Aoyama-sensei is keenly aware of the importance of the glaze, even though he stresses that the clay is the most critical factor in the creative process.

"Yes, the glazing is important, but let me show you these samples to show you something," he says, and puts these two cups on the table:

"I saw signs of a connection. To begin with, there are these unique cracks or lines in the glazing of Onada pottery that are also visible on the cups in the museums. Previously the consensus was that too long firing must have caused them, but we now know they appear because of the way the ash glaze penetrates the ceramic material during the firing. It's a phenomenon particular to the interplay between the ash glaze and a particular kind if clay. That clay only exists here in Onada.”

Ash glazes are ceramic glazes made from the ash of various kinds of wood or straw. The glaze has glasslike and pooling (buildup of glaze) characteristics which put emphasis on the surface texture of the piece being glazed. Wood ash glazes result in mostly dark brown to green colours. The Onada potters used a Kiseto variant of glaze that interacted with the clay chemically, resulting in a white finish. Aoyama-sensei is keenly aware of the importance of the glaze, even though he stresses that the clay is the most critical factor in the creative process.

"Yes, the glazing is important, but let me show you these samples to show you something," he says, and puts these two cups on the table:

"Look at these two samples," he says. "Why do they look so different, do you think? Because of the glazing? You may be surprised to know that they have exactly the same glazing. One looks very shiny, one looks matte, and it is because the ceramic material under the glaze is different. This is why the clay is so important for the finish, and the clay was the most important reason to establish a kiln in the old days."

We are beginning to see how important the clay is for the signature of the Shiro Tenmoku. These are the the kind of things that Onada-sensei have absorbed from the earth in Onada.

What about the shape, then? The crooked lines of shiro tenmoku - in Aoyma-sensei's view the beginnings of the even more irregular shapes of Oribe ware - seems to have to do with the pottery technology of the time. Potter's wheels were not equipped with a motor, like today, but spun by hand. The lesser speed and torque made a different technique necessary from what is common today. Instead of placing a lump of clay on the wheel and shape it while spinning it at high speed, potters of the day seemed to first have made a stand from clay, like an upside down flower pot. Next they shaped the clay into a rough shape using a coiling technique in which clay was rolled into long threads that were then pinched and beaten together to form the body of a vessel.

Only in the next step did they turn the wheel, and with a rough shape already done they could finish the design with much less force and speed than necessary to spin the wheel to shape a lump of into a cup. The preferred technique among Mino potters was thus hand-building. "The reason for using this method was simple," Aoyama-sensei explains. They hand-powered the wheel, so it would be both impractical an energy-consuming to try to spin the wheel during the whole process. In China and elsewhere, including many places in Japan, potters used a kick-wheel for more speed. Another difference is that the Chinese tend to shape the vessels by turning, like when you use a lathe. A non-rotary tool bit is used, moving more or less linearly while the work piece rotates. This makes it possible to create shapes with perfect symmetry, but for this to work the vessel must by dried to some extent first. Japanese potters do not shape their pottery by turning, neither the inside nor the outside of the vessel."

This would explain the asymmetry of Japanese pottery, and in particular Mino ware. The classic Mino potters never adopted the advanced pottery technologies. Instead, market forces came to rescue. The increasing popularity of wabicha created a demand for pottery with irregular shapes. This was true for Shiro Tenmoku, according to Aoyama-sensei, as well as for other tea utensils. We know how this later would develop into radical asymmetry in the form of Oribe ware. But that is another story.

We are beginning to see how important the clay is for the signature of the Shiro Tenmoku. These are the the kind of things that Onada-sensei have absorbed from the earth in Onada.

What about the shape, then? The crooked lines of shiro tenmoku - in Aoyma-sensei's view the beginnings of the even more irregular shapes of Oribe ware - seems to have to do with the pottery technology of the time. Potter's wheels were not equipped with a motor, like today, but spun by hand. The lesser speed and torque made a different technique necessary from what is common today. Instead of placing a lump of clay on the wheel and shape it while spinning it at high speed, potters of the day seemed to first have made a stand from clay, like an upside down flower pot. Next they shaped the clay into a rough shape using a coiling technique in which clay was rolled into long threads that were then pinched and beaten together to form the body of a vessel.

Only in the next step did they turn the wheel, and with a rough shape already done they could finish the design with much less force and speed than necessary to spin the wheel to shape a lump of into a cup. The preferred technique among Mino potters was thus hand-building. "The reason for using this method was simple," Aoyama-sensei explains. They hand-powered the wheel, so it would be both impractical an energy-consuming to try to spin the wheel during the whole process. In China and elsewhere, including many places in Japan, potters used a kick-wheel for more speed. Another difference is that the Chinese tend to shape the vessels by turning, like when you use a lathe. A non-rotary tool bit is used, moving more or less linearly while the work piece rotates. This makes it possible to create shapes with perfect symmetry, but for this to work the vessel must by dried to some extent first. Japanese potters do not shape their pottery by turning, neither the inside nor the outside of the vessel."

This would explain the asymmetry of Japanese pottery, and in particular Mino ware. The classic Mino potters never adopted the advanced pottery technologies. Instead, market forces came to rescue. The increasing popularity of wabicha created a demand for pottery with irregular shapes. This was true for Shiro Tenmoku, according to Aoyama-sensei, as well as for other tea utensils. We know how this later would develop into radical asymmetry in the form of Oribe ware. But that is another story.

The challenge of recreating shiro tenmoku

As mentioned before, Aoyama-sensei was convinced that the classic shiro tenmoku owned by the museums must have been produced in Onada. “The “cat whiskers” effect typical for pottery from Onada is unique to firings with ash glazing in combination with clay only available here," he explains. "These 'whiskers' are clearly visible also in the museum owned pieces. Seeing these signs of commonality I became determined to try to recreate shiro tenmoku from local material using local Onada methods. To do that I would have to find clay identical to what the Onada potters used many centuries ago. After searching diligently, I finally found it at two locations, one near the Hakusan Shrine (which was built near the Hakusan kiln ruins) and the other in the vicinity of a golf course.”

“Then there was the matter of the glazing. I was convinced that ash glazing in combination with Onada clay is key to achieve the shiro tenmoku look with the cat whiskers signature and whiteness typical of this pottery. Pottery produced at the Hakusan kiln, the Amagane kiln, as well as the Kamashita kiln here in Onada all have this cat whiskers signature in the glazing.”

“Then, in 1994, there was an excavation close to my workshop in Onada, and they found very whitish cups. This was it! This must be the birthplace of shiro tenmoku! I was anxious to get a look. Did the cups have ash glazing and the cat whiskers signature? An academic who was a friend of mine was involved in the diggings, and I pestered him about the cups, but he wouldn’t let me see them. It was quite frustrating, because he had always told me it would be tough to find shiro tenmoku cups, and now they were so close! He resisted my pleadings. ‘We have to report the news to the media first, he said.’”

“When the story had been published, I could finally see the cups, and immediately told the professor I was confident I could do a faithful reproduction. He agreed to the plan, and I made a white cup and brought some of the clay as well to show him. Naturally, the cups found in the diggings looked nothing like they must have done when they were in use. After decades or centuries of use followed by an even longer time in the earth, pottery is bound to change its appearance. To show that my reproductions were true to the originals as they must have looked after years of usage, but before being buried in the ground, we would have to wait for the change to happen in them.”

“Then there was the matter of the glazing. I was convinced that ash glazing in combination with Onada clay is key to achieve the shiro tenmoku look with the cat whiskers signature and whiteness typical of this pottery. Pottery produced at the Hakusan kiln, the Amagane kiln, as well as the Kamashita kiln here in Onada all have this cat whiskers signature in the glazing.”

“Then, in 1994, there was an excavation close to my workshop in Onada, and they found very whitish cups. This was it! This must be the birthplace of shiro tenmoku! I was anxious to get a look. Did the cups have ash glazing and the cat whiskers signature? An academic who was a friend of mine was involved in the diggings, and I pestered him about the cups, but he wouldn’t let me see them. It was quite frustrating, because he had always told me it would be tough to find shiro tenmoku cups, and now they were so close! He resisted my pleadings. ‘We have to report the news to the media first, he said.’”

“When the story had been published, I could finally see the cups, and immediately told the professor I was confident I could do a faithful reproduction. He agreed to the plan, and I made a white cup and brought some of the clay as well to show him. Naturally, the cups found in the diggings looked nothing like they must have done when they were in use. After decades or centuries of use followed by an even longer time in the earth, pottery is bound to change its appearance. To show that my reproductions were true to the originals as they must have looked after years of usage, but before being buried in the ground, we would have to wait for the change to happen in them.”

“I finished a reproduction in the year of 2000, which I thought was very close to the originals. I had glazed it with haigusuri - ash glaze - of kiseto type, similar to a cup found at the Hakusan kiln. I made one more reproduction for the professor, and we used them daily until 2012. By then we could see how they had begun to show clear signs of ageing - keinen as we say in Japanese. Finally, we felt confident we could show the world a true Shiro Tenmoku, reproduced with the techniques and materials used at the old Onada kilns. We could show how it looked virtually identical to the two cups listed as Important National Treasures.

"Take a look at a piece from the Tokugawa Art Museum in Nagoya in this book. I will put a reproduction I made on top of it. You probably even have trouble telling which is which,” he says, laughing. “Note the cracks in the glazing of both pieces."

From the results of analysing the ash glaze used to reproduce shiro tenmoku tea bowls, it was also found that apart from the clay, the glaze is an additional factor that contributes to the whiteness of shiro tenmoku. Professor Toshitaka Ota who contributed to the analysis suggested that shiro tenmoku appears white due to the concentration of potassium at the contact point between the substrate ceramic material and the glaze layer. In other words, as a result of the fusion of the whitish clay and a glaze rich in potassium, the glaze becomes remarkably white. It is thought that the white colour of the tenmoku tea bowls excavated from the Onada Kamashita kiln ruins is a result of this phenomenon.

It is the consensus in Japan today that only by using the clay in Onada and the ash glazing practised at the ancient kilns in the village is it possible to produce shiro tenmoku cups like those listed as Important National Treasures by the government. The idea of shiro tenmoku being Shino was finally abandoned after the results produced by Aoyama-sensei and his collaborators.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE DISCOVERY

Something happened in the transition between the Muromachi period, where the tea ceremony first took root as a treasured event for the elite in Japan, and the Momoyama period. By Momoyama times, tastes had shifted towards the native Japanese sensibilities. As Anna Willmann of the Metropolitan Museum writes about Momoyama pottery:

[Their] flamboyant decoration indicates a shift in style at the time, and reminds us of the constant quest by tea practitioners to find new assemblages to intrigue and surprise their guests.

Before this shift, an admiration of Chinese culture and the treasures brought to Japan had set the tone. The Chinese were able to produce perfectly symmetric shapes, a result of millennia of technological development. But gradually the Japanese turned their attention to native unglazed stonewares first intended as utilitarian vessels for farmers. Willman writes:

[...]tea masters began to incorporate rustic ceramic vessels from Korea and Japan, and found beauty in unrefined, natural, or imperfect forms. By the authority of their recognized connoisseurial abilities, the leading tea men of the time elevated these objects to the same level as the ancient Chinese treasures. This aesthetic, which celebrates austerity, spontaneity, and apparent artlessness, is known as wabi.

The culmination of this was the creation of "new types of wares, such as Raku, Shino, and Oribe". They were handmade bowls, "thought to better reflect the spirit of the maker than something thrown on a wheel". And Willmann continues:

As opposed to agrarian vessels that were created by unknown potters, this type of ceramic puts more emphasis on the creator’s role in the process.

Craftsmanship was very much in focus, the skills needed were different from those in the Chinese tradition. Shino and Oribe originated in Mino, the home province of Onada. Oribe, in particular, were warped or seemingly flawed wares. Where does this leave Shiro Tenmoku? These white cups seem to have some of the symmetry of the classic Chinese wares, and yet also some of the asymmetry of this new trend. They were not Shino. It seems that we have here something very different, a form that has yet to be recognized by most Western commentators, but finally highlighted by people like Aoyama-sensei and now highly treasured in Japan.

Aoyama-sensei's message to the world

Given the fact that the awareness of the true origin of shiro tenmoku has yet to reach the West, what does Aoyama hope a Western audience can learn from this?

“It is true,” he replies, “that the history of pottery in Japan has undergone a vital review over the last years. However, there are other things also worth thinking about. I often ask myself how pottery in Japan would have developed if the Shiro Tenmoku had never existed, or the other forms of asymmetrically shaped pottery. Would the now so famous fantastic shapes of the Momoyama pottery ever have appeared on the scene? After all, the famous Shino and Oribe pottery that first saw light in the Mino region came into existence because of a centuries-long development preceding the Momoyama era. Now we know that shiro tenmoku is not part of the times of Shino or Oribe, but of a period leading up to those times. One that gave birth to the Mino ware renaissance and radical new designs.

My lifework is to deepen my understanding of this, to spin the wheel and make pottery, exploring techniques of the past. I work to re-engineer the old yamajawan production techniques as well as those of sueki, which originated in Korea. I go deeper and deeper into the old techniques for ash glazing. And doing so, absorbing secrets from the grounds of Onada, I learn, and I adopt those techniques to create my pottery for people to enjoy now and in the future.

Notes

- “Turning Point: Oribe and the Arts of Sixteenth Century Japan”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, edited by Miyeko Murase, p. 33

- 東京国立博物館本『七十一番職人歌合』二十四番 「一服一銭」と「煎じ物売」

- “Turning Point: Oribe and the Arts of Sixteenth Century Japan” , p. ...

- Shino, Kiseto, Setoguro, Volume 11, Heibonsha, 1989, Toyozō Arakawa, p 89

- Ibid, pp 88 - 91

- Fire clay is resistant to high temperatures, having very high fusion points. Because of its stability during firing in the kiln, it can be used to make complex items of pottery.

- Bidoro glaze is a glass-like glaze formed by ash.

- Data from "Shiro Tenmoku - the Reproduction of Ash Glazed Old Ceramics" 白天目:灰薬古陶の再現. Pamphlet published by Mino Ceramic Art Museum, Tajimi.

- Anna Willmann, Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Essay, "The Japanese Tea Ceremony", April 2011

For more background, see this older story in which Aoyama-sensei discusses the developments that led to Shino and Oribe ware.