Kasahara - the tile kingdom

By Hans O. Karlsson

This is a story of a humble pottery town that transformed into a tile production centre, then declined and now attract tourists against all odds.

Kasahara is a small community in Tajimi, Gifu Prefecture. It is an industrial town, admittedly not pretty in all places with all it’s dull looking factories with walls made from corrugated galvanised iron. But it does have it’s beauty spots - as we shall see - and in between the factories people always seem to be able to squeeze in little gardens where they grow all kinds of vegetables and other things. Plants love the hot and humid climate here.

This town is an example of the economic miracle that took place in Japan after the Second World War. After its defeat, the country was occupied by the victorious allied forces. Paradoxically, this would lead to a golden age for the tile industry in this little town in Gifu Prefecture. The region is rich in clay highly suitable for the production of ceramics, a local tradition that goes back a millennium. This was the foundation for the industrialization of Kasahara. When the country entered its era of rapid modernization in the second half of the 19th century, there was a shift in the area from older methods to industrial production of rice bowls. By the time the country had risen to be a power in East Asia more profitable tile production had begun to take root.

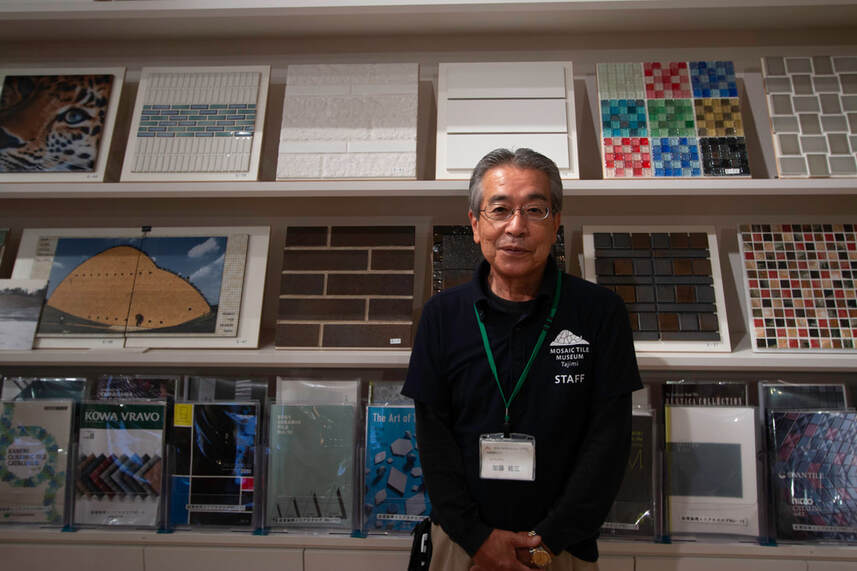

A key person in this change was Itsuzo Yamauchi, who was born in Kasahara in 1908. Yamauchi had discovered the possibilities of decorative tiles during his studies at the Kyoto City Ceramic Research Institute. After his return home, he began development of glazed porcelain mosaic tiles, making an important mark in this early stage of the local industry. But it was a foreign influence that changed the destiny of the small town. Nodoka Murayama, the curator of the Mosaic Tile Museum, explains why: “When the Allied Occupation Forces started to move into buildings around Japan they needed to restore their interiors. They ordered large quantities of tiles for this purpose.” Until this time tiles had been used by the Japanese in bathrooms and kitchens because of their water resistance, resistance to dirt and easy cleaning. Small tiles were practical because they were easy to apply to curved surfaces. “Now makers realised,” Murayama explains, “that foreigners too used tiles in their buildings, and sometimes in different ways. In the US, for example, there was a large market for tiles for private swimming pools”.

The currency market played into the hands of Japanese exporters. Masaki Mizuno is the CEO of Ceramesse, a large tile maker in Kasahara. He has a 40-year career in the industry and is quite familiar with its history. “In these early post-war days,” he explains, “the yen stood at only 360 to a US dollar, and that was a huge contributing factor to the post-war export boom for Japanese tiles.”

Realising the great opportunity, many of the rice-bowl producers began to change to tile manufacturing. One of them was Mizuno’s father. “Pottery has historically been as natural a source of income to people here as farming is in many other rural areas in Japan,” he says. “High-grade clay can be found everywhere in the mountains. To build a kiln and produce ceramics was an obvious way to make a living here. But now people discovered a way to make a product of higher added-value that could bring in dramatically greater profits. My grandfather convinced my father to set out on this new venture.”

“These were good times in Kasahara", he continues. “Company owners would go down to Kyushu [the southernmost main island in Japan] to find people who would work in their factories. They brought back young people, many teenagers, who had little education and needed a stable income. Many were chosen after a recommendation by their teachers. I remember how they would hang around in Kasahara on Sundays when they were off, or near our company dormitory. Many of the local kids were curious and spied on them, and when they were discovered by their fathers they would take a beating. These young people were poor, they couldn’t even afford a bicycle to get around. Company owners felt a responsibility to take on the role their parents would normally have and helped out as go-betweens to arrange marriages. In these days of rapid growth, Kasahara would get as many as two thousand new workers every year. My father was always busy and rarely had dinner with us at night. He and other factory owners were always on the hunt for new workers, often down in Kyushu. But I had no desire to work in our factory. The work was dangerous, dirty and exhausting.”

Mizuno eventually ended up as the CEO of the family business, but only did so very reluctantly. “I had spent my teenage days away from my family, first in Nagoya where I lived alone in the school dormitory, and later in a university dormitory in Tokyo,” he explains. “I finally decided that a white-collar job in the over-crowded capital was not for me, but when I returned home it was hell for the first years. I cried a lot and escaped in my free time to my old school friends in Nagoya. But as time moved on and everyone got married and settled down, I finally resigned to the fact that my future was in the tile business.”

It all sounds quite dark, but my overall impression of Mizuno is one of a kind, friendly person. He gives the impression of someone with solid insight into his industry. He replies to my questions in a very polite and articulate way - never hesitates or looks for ways to impress us. It makes me feel, somehow, that he was the right person for the job all the way.

It all sounds quite dark, but my overall impression of Mizuno is one of a kind, friendly person. He gives the impression of someone with solid insight into his industry. He replies to my questions in a very polite and articulate way - never hesitates or looks for ways to impress us. It makes me feel, somehow, that he was the right person for the job all the way.

How the roof tiles of the museum were created

Mizuno's career in the industry started when the good days after the war was already over. Japan started to be outcompeted by countries like China and Malaysia where production was cheaper. “To be honest, I have never felt for a moment that we are doing well, or that the future is bright,” he says. “Every day I worry about next months sales. And even if they are good, will we stay in the black next year? Or the year after that? I guess it’s just my personality.”

There was another golden age yet to come for Kasahara. It was the economic bubble that started in the 1980s. “The peak days for the tile industry came in 1991 - 92,” Mizuno says. The Japanese economy was booming again and growth was strong and constant. High-rise buildings were shooting up everywhere, and as now tiles had become a common material for exteriors, the exploding construction activity around the country created a need for massive production. The demand was insatiable, and the local economy in Kasahara boomed. Everyone was making tiles, and still, it was hard to keep up with the demand. We had a hard time finding enough raw material. But I was still always worried and stressed.” Perhaps this is the reason for his company doing so well even after the bubble burst.

“Times are very different now,” he says. “We can not compete with the mass producers in China or Malaysia. We must focus on producing what they can’t - products that don’t fit into their business model of low prices and high volume. Those are highly refined products, expensive but with a special look that can add refinement to an interior, for example. If the design is sophisticated and suits the customer’s taste and the price not unacceptably high, they will buy. But in the large volume markets, we stand no chance. I would say today Japan probably only has two per cent of the US market for example.

the mosaic tile museum

“This is the reason we have rearranged our displays on the showroom floor of the Tile museum,” comments Murayama. "Before we just showed a large number of samples to prospective customers. Now we have built full interiors with tiles used precisely like that - accents in kitchens or bathrooms and so forth. This way visitors can get a much better impression of how the tiles work as part of an interior as a whole.”

People wanted to keep the identity of the tile town alive and try to invigorate its industry and community again. Could a museum help in that effort?

The idea of the museum was brought forward around the shift of the century when the second boom in the tile industry had long been over. The once-thriving town of Kasahara was now facing dire times. The town was close to becoming incorporated into neighbouring Tajimi, but people wanted to keep the identity of the tile town alive and try to invigorate its industry and community again. Could a museum help in that effort?

“I believe many locals thought it was a rather wild idea,” says Mizuno. “Who would ever want to visit a tile museum?”. “Tajimi city was not very keen on the idea, either,” he says. “There are so many cases around Japan of wasteful spending of taxpayer money on vanity projects. But we were steadfast on our side. The city had agreed to finance the museum in principle, and if they withdrew their money we would need to rethink the merger. They finally backed down but there was still a hard battle to be fought over the choice of architect, and not the least the design. When the winning idea was finally presented, even the locals thought it was to far out there!”

But the museum got built, and it opened its doors after two decades of debate and plans close to being ditched several times. Tajimi city had agreed to finance the museum and its operation, except the second floor. We will come back to that later, but in essence, it is a space for the exhibit and sale of tiles from local makers. The rest of the museum serves to preserve and promote the culture of Kasahara, so public funding is justified. Even so, many had doubts this would be a wise investment. To everyone’s surprise, there was a steady stream of visitors from day one.

“I think the museum must have come at the right time and in the right shape,” says Mizuno. “The design is radical,” he says, “but it is gentle and melds building and nature.” In fact, there are many places around the mountains in Tajimi that has a similar shape, after decades of carving clay from the hillsides. The clay is laid bare on one side and on the top, there is still vegetation. “There is a romantic feel to it,” Mizuno says, smiling. “It is even cute in a way”. Cute, or kawaii in Japanese, is a concept loved by many young Japanese women, and they are very visible segment of the visitors to the museum. In particular, you will find many enjoying themselves in the DIY workshop corner on the first floor.

What else can you see at the museum? The tour starts on the fourth floor with a display of household objects and decorations preserved from the past. There are sections of tiled walls from public bathhouses, tile clad kitchen sinks, toilets and so forth. You will find a number of bathtubs that look impossibly small to a Westerner.

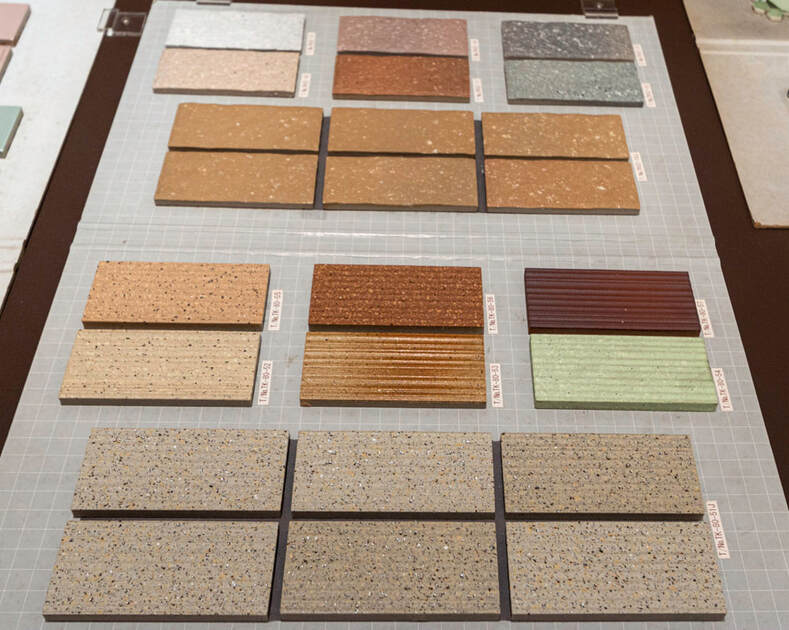

Many of the tiles here feel like artefacts from yesteryear. Colours and patterns feel very “retro”. Tiles on this floor all come from the age when their main application was to provide protection from water and easy maintenance inside buildings. This was how tiles were mainly used in the early post-war days.

Many of the tiles here feel like artefacts from yesteryear. Colours and patterns feel very “retro”. Tiles on this floor all come from the age when their main application was to provide protection from water and easy maintenance inside buildings. This was how tiles were mainly used in the early post-war days.

By contrast, there is a large hole in the ceiling that feels radical and new. What will happen when a typhoon drops massive amounts of water through that thing?, I wander. “Everybody baulked at that design”, Mizuno says, but the architect insisted on having it this way. I can see what he was after. Seeing all that sky above us makes the small space feel open and unconstrained.

The 3rd floor is more dynamic in the sense that its contents are changed regularly. The exhibitions here are designed according to three themes: the production of tiles, the history of the town of Kasahara, and tiles in architecture. “Visitors change, too, depending on what we have on display,” says Murayama. “Some time ago we had an exhibition of works by young artists using a unique method to create very visually appealing works. It attracted many young visitors. Later we had an exhibition of tiles used in temples in the Edo era (1603 - 1868) and the following Meiji era. That was apparently more attractive to an older audience.” At the time of our visit, the exhibitors took us on a historic journey of the industry in Kasahara, from the early days through the booming years of the 80s and early 90s with mass production of tiles for exteriors.

One stair down on the showroom floor we enter the modern age. Little showrooms have been built to showcase how tiles can be used as accents in modern living spaces. If you remember, Mizuno said that today’s customers are looking for “highly refined products, expensive but with a special look that can add refinement to an interior.” This floor has become an attraction where people like to take selfies in front of the various simulated living environments.

Finally, on the first floor, we find the tile experience corner, where people can try their hand on assembling patterns with tiles of their choosing. It is very popular among young women and families. “Unfortunately many individual foreign visitors tend to skip this part,” says Murayama. “It is most likely because of the lack of guidance in foreign languages.”

We ask her how she would like the museum to develop in the future. “That is something we must work with the community on,” she says, “but I think it would be wonderful if we could connect artists to local makers so they can experiment with new designs and applications. In fact, I hope we can integrate the museum better with its surrounding community as a whole. There are more places of interest around here that many visitors miss out on.”

Mizuno agrees: “We have a wonderful park for cherry blossom viewing very close, for example", he says. People can enjoy a picnic in a tranquil and beautiful environment with a great view all the way to the sea.”

On our way back we drive slowly through an alley once full of life and commercial activity - the Ginza doori (alley). There is an ancient-looking book shop, still open for business. My wife points out where other shops once lined the street, which is the approach to the local, rather impressive Shinto temple in Kasahara. “Over there was once a shop that sold goldfish,” she says, pointing with her finger. “And further down this street was a toy shop. All the kids loved this place.”

We stop by the place of worship and take a look at the tile art there, a work by the famous Itsuzo Yamauchi. Like so many other jewels in this town it is not easy to find. But I guess now you have a clue of where to look, and maybe you will go on your own exploration the day your path takes you to the tile kingdom of Japan.

related links

- The Mosaic Tile Museum

- Article on flower viewing in the Shiomi no Mori Park

- More articles about ceramics and local culture in Tajimi

contact

Contact us about travel to and experiences in Tajimi