part two

Three ancient Shiro Tenmoku tea bowls were introduced as the theme in the first installment of this article. Originally owned by the medieval tea master Takeno Jōō, they have seen the nation take shape across centuries. The bowls passed through the hands of some of the giants in Japan’s cultural and political history. Moreover, they are believed to be a rare example of pottery originating in Japan. Master potter Sokei Aoyama spent decades trying to reproduce the bowls and confirm their origin. He was particularly interested in two of Takeno's bowls. They are listed as Very Important Cultural Assets by the government. The potter suspected they were made in his home village, Onada in Tajimi city. He also found clues indicating that they are not part of the Shino ware tradition, contrary to the consensus at that time. In this second part of the article, we will learn how he arrived at this conclusion.

Pottery is first of all the union of clay and other raw materials combined into a single shape. The potter is limited to play second or even third fiddle. That is the thinking of Sokei Aoyama, experimental archaeologist and potter in Onada, a village in the city of Tajimi, Japan.

“According to an old Japanese saying,” he explains, “‘First comes the clay, then the kiln, and last the potter’s skill’ (ja: 一に土、二に窯、三に細工). This is why nearby clay resources were so important to potters of the past. For example, in Takata, Onada’s neighbouring village, kilns have produced tokkuri (sake jars) since the middle of the Edo period (1603 - 1868). The reason is that the clay in the area is suitable to make vessels for liquids.”

“According to an old Japanese saying,” he explains, “‘First comes the clay, then the kiln, and last the potter’s skill’ (ja: 一に土、二に窯、三に細工). This is why nearby clay resources were so important to potters of the past. For example, in Takata, Onada’s neighbouring village, kilns have produced tokkuri (sake jars) since the middle of the Edo period (1603 - 1868). The reason is that the clay in the area is suitable to make vessels for liquids.”

Takata clay is very resistant to permeation. Because of this, Tokkuri made in Takata can hold sake without leaking for very long periods of time. During the Edo period, sake trade flourished. The drink must be transported and stored for consumers in the one-million city of Edo and other far-away markets. The clay in Takata thus provided the raw material for mass-market tokkuri.

Aoyama-sensei suspected that there were clay deposits somewhere in Onada similarly suitable for the production of Shiro Tenmoku. He had a hunch that Onada may have been the origin for Takeno's bowls. Perhaps if one used this clay and the production methods common in the area in medieval times, it would be possible to reproduce bowls similar to the museum pieces? If this theory was correct, the project must start by locating suitable clay deposits.

Onada is located in Tajimi city, Gifu, Japan. It is part of the historic Mino region, famous for Mino ware such as Shino and Oribe. Note: Google incorrectly names Hakusan Shrine "Shirayama Shrine".

The diggings in 1994 (see Part One) resulted in a find of a white chawan at the ruins of Onada Kamashita Kiln Number 6. Notably, the clay used for the excavated chawan seemed to be somewhat different from that of Shino ware.

Traditionally, so-called “moxa [eng: Mugwort] soil” that can be found at Gotomaki (ja:五斗蒔) or Ōgaya (ja:大萱) in Toki city has been used for Shino ware (Note 01). This results in the soft, organic look for which Shino is famous. The excavated white bowls, on the other hand, had a very solid and hard feel to them. Aoyama-sensei asked to have a scientific analysis done, comparing ceramic body material typically used for Shino ware to the body content of a Shiro Tenmoku chawan he reproduced. He selected clay for the latter from local deposits, by inference of what was realistically available to Onada potters in the Muromachi period (1392–1573). This was the time of Takeno Jōō and the first historical record of Shiro Tenmoku.

Ceramic materials as a percentage of total body content

Feldspar |

Clay |

Quartzite |

Others |

|

Typical Shino ware* |

6.56 |

31.37 |

61.07 |

0.49 |

Shiro Tenmoku chawan** |

10.77 |

48.52 |

40.71 |

0.81 |

*) Date provided by the Izumi Ceramics Manufacturing Association (ja: 泉陶磁器工業協組).

**) Estimated composition. The clay was collected at Takata Iwatogoe (ja: 高田岩ヶ峠). Source (pamphlet): "Tajimi City Minoyaki Museum Exhibition: The Recreation of Shiro Tenmoku Ancient Ash Glazed Pottery" (ja: 白天目 灰釉古陶の再現)

**) Estimated composition. The clay was collected at Takata Iwatogoe (ja: 高田岩ヶ峠). Source (pamphlet): "Tajimi City Minoyaki Museum Exhibition: The Recreation of Shiro Tenmoku Ancient Ash Glazed Pottery" (ja: 白天目 灰釉古陶の再現)

the differences between shiro tenmoku and Shino glazing

Aoyama-sensei speaks about the results from the diggings:

“In the excavation near the Kamashita kiln No. 6 four incomplete white chawan were discovered. One or two had previously been found at kiln No. 1. Among these incomplete bowls, one was pure white, while four had a light green colour. There was also one brownish item. Among these items some were thought to be similar to the original Shiro Tenmoku, while others were not.”

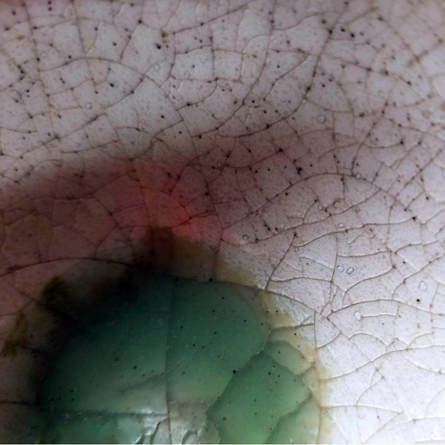

“There is an easy way to determine if there is a relation to the originals,” he says. “You need to look for “cat whiskers cracks” in the glazing (kanyuu, ja: 貫入].” He rummages around in his workshop for a while and finds an ancient looking piece of broken pottery.

“In the excavation near the Kamashita kiln No. 6 four incomplete white chawan were discovered. One or two had previously been found at kiln No. 1. Among these incomplete bowls, one was pure white, while four had a light green colour. There was also one brownish item. Among these items some were thought to be similar to the original Shiro Tenmoku, while others were not.”

“There is an easy way to determine if there is a relation to the originals,” he says. “You need to look for “cat whiskers cracks” in the glazing (kanyuu, ja: 貫入].” He rummages around in his workshop for a while and finds an ancient looking piece of broken pottery.

“Take a look at these cracks,” he says. “Cracks in glazing are called kan'nyū (eng: penetration). This piece was found in Onada. The cat whiskers kan'nyū are very notable.” They are very long, horizontal, wiggly lines, quite different from the other, shorter cracks covering the inside of the bowl."

The interesting thing was that the museum owned Shiro Tenmoku and pottery discovered in Onada shared this feature. Aoyama-sensei explains: “The very long, horizontal kan'nyū cracks are a signature feature found both on pottery excavated in Onada and the original, museum owned bowls. Previously it had been thought that they were the result of excessive firing. Now we know they appear because ash glaze penetrates the surface of the ceramic material during the firing. It's a phenomenon caused by the interplay between ash glaze and a particular kind of clay. It has to do with how the ceramic material and the glaze expands at different rates in the heat. That is the reason for these unusual "cat whiskers" glaze penetration cracks.” While kan'nyū commonly appear on pottery, these long cracks, "cat whiskers" as Aoyama-sensei calls them, gave him reason to suspect that the medieval potters of Onada were indeed the creators of Shiro Tenmoku.

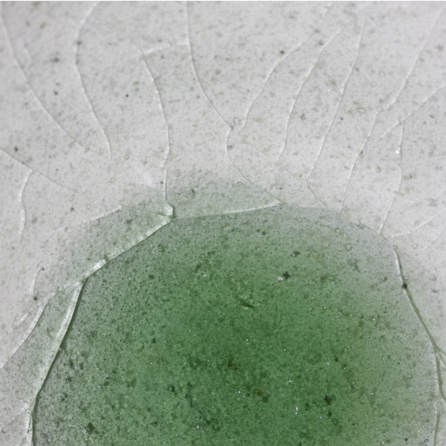

Aoyama-sensei brings another piece. It looks quite different at first glance. “Now, let’s compare to a piece of Shino ware. As you remember Shiro Tenmoku has traditionally been regarded to be Shino ware.” I take a close look. The cat whiskers cracks - the most prominent feature of the Shiro Tenmoku piece - are nowhere to be seen in the Shino ware sample.

Another distinguishing feature between the two forms of pottery are the bubbles (ja: 気泡) in the glazing. They are very visible in the Shiro Tenmoku because of the transparency of the glazing, while the more clouded glazing of Shino makes them harder to see.

If one looks closely the bubbles in the Shino glazing tend to connect to each other. The bubbles in the Shiro Tenmoku, on the other hand, are clearly separated.

“The first time I saw one of the original Shiro Tenmoku,” Aoyama-sensei says, "I was unaware of Arakawa-sensei’s view of Shino ware." As mentioned in Part 01, Toyozō Arakawa, a well known Japanese potter, believed Shiro Tenmoku to be Shino, and wrote about it years later (Note 02). "The glazing on the chawan in the museum brought to mind natural ash-glazed pieces (ja: 自然釉) discovered in Onada. I wondered if the chawan in front of my eyes in the museum might be ash glazed as well. There was an incomplete chawan that had been found by a collector before the excavation in Onada. It was discovered near the Onada Kamashita kiln number 1. I had heard rumours that it, too, had ash glazing.

“One more thing pointed to ash glazing. About this time I had been glazing pottery with feldspar from the river bed of the Toki river. From this experience I knew that it wasn’t possible to produce a light green, transparent glazing using feldspar.”

"first is the earth"

Ash glazes are ceramic glazes made from the ash of various kinds of wood or straw. The glaze has glasslike characteristics and builds up on the surface texture of the piece being glazed, seeping into it. Wood ash glazes result in mostly dark brown to green colours. The Onada potters used a glaze with a glass-like, transparent quality. It interacted with the ceramic material, resulting in a white bowl. Aoyama-sensei recognises the role of the glaze in the outcome of the creative process in pottery. Still, it is apparent that he is very much a believer in the overall importance of the earth used for the ceramic body.

"Yes, the glazing is important, but let me show you these samples," he says, and puts these two cups on the table:

"Look at these two samples," he says. "Why do they look so different, do you think? Because of the glazing? You may be surprised to know that they have exactly the same glazing! One looks very shiny, one looks matte, and it is because the ceramic material under the glaze is different. This is why the clay is so important for the finish. That is why the most important reason for the location of a kiln in the old days was that suitable clay was available there."

What about the shape, then? The crooked lines of Shiro Tenmoku - in Aoyama-sensei's view the beginnings of the even more irregular shapes of Oribe ware - seems to have to do with the pottery technology of the time. Potter's wheels were not equipped with a motor, like today, but were hand powered. The lesser speed and torque made a different technique necessary from what is common today. They shaped the clay into a rough shape using a coiling technique in which clay was rolled into long threads that were then pinched and beaten together to form the body of a vessel. The result is a shape with imperfections, such as lines in the outside and inside walls of the bowl and less overall symmetry than if a high-speed potter's wheel is used.

THE CHALLENGE OF RECREATING SHIRO TENMOKU

As mentioned above, several clues pointed to a link between the museum owned Shiro Tenmoku and the kilns of Onada: the “cat whiskers”, the glazing, the way it interacts with the ceramic body resulting in a white bowl. Aoyama-sensei was convinced that the right kind of clay must exist somewhere in Onada. “I became determined to try to recreate Shiro Tenmoku from local material using local Onada methods. To do that I would have to find clay identical to what the Onada potters used many centuries ago. After searching diligently, I finally found it near an old kiln and at another nearby location.”

“Then there was the matter of the glazing. I was convinced that ash glazing in combination with Onada clay is key to achieve the Shiro Tenmoku look with the cat whiskers signature and whiteness typical of this pottery. Pottery produced at all the old kilns of Onada - the Hakusan kiln, the Amagane kiln, as well as the Onada Kamashita kiln - have this cat whiskers signature in the glazing. This pointed to that they all used the same raw materials.”

“Then there was the matter of the glazing. I was convinced that ash glazing in combination with Onada clay is key to achieve the Shiro Tenmoku look with the cat whiskers signature and whiteness typical of this pottery. Pottery produced at all the old kilns of Onada - the Hakusan kiln, the Amagane kiln, as well as the Onada Kamashita kiln - have this cat whiskers signature in the glazing. This pointed to that they all used the same raw materials.”

“When they found white bowls in the 1994 excavation I thought: ‘This is it! This must be the birthplace of Shiro Tenmoku!’ I was anxious to see them. Would the bowls have ash glazing and the “cat whiskers” signature? Shōji Taguchi (ja: 田口昭二氏), an archaeologist with the City of Tajimi who was a friend of mine, was involved in the diggings. I pestered him about the bowls, but he wouldn’t show them to me. It was quite frustrating. He had always told me it would be next to impossible to find Shiro Tenmoku bowls, and now they were so close! He resisted my pleadings. ‘We have to report the news to the media first, he said.’ I suppressed my yearning to see the bowls and waited, patiently, for my moment.”

“When the story had been published, I could finally see the bowls. When I did I was excited to find the pieces to be very similar to the ones on the bowls in the museums. I now felt confident that the Shiro Tenmoku discovered in the Onada excavation and the famous museum pieces had much in common. I immediately let an expert know that I was sure I could reproduce bowls true to the originals. He agreed to the plan. I began a trial and error process of making white bowls, having them inspected by the professor, and trying again, over and over.

“Finally, in the year 2000, I had produced a bowl with an appearance very close to the originals. I used a transparent, glass-like ash glazing very similar to the that used on the bowls found near the Onada Kamashita kiln. Feldspar resources in Onada are more or less nonexistent. For this reason, I used very little feldspar in the glazing. I applied it to a ceramic body made from earth collected in Onada. Because of the different rate of contraction in the glazing and the ceramic material underneath when firing, cat whiskers cracks appeared. I was also able to reproduce the bubbles [see above] in the glazing.”

A scientific analysis of the reproductions was conducted. The pamphlet “Tajimi City Minoyaki Museum Exhibition: The Recreation of Shiro Tenmoku Ancient Ash Glazed Pottery”, outlines the results:

”From the results of analysing the ash glaze used to reproduce Shiro Tenmoku tea bowls, it was found that apart from the clay, the glaze is an additional factor that contributes to the whiteness of Shiro Tenmoku. Professor, Toshitaka Ota, who contributed to the analysis, suggested that Shiro Tenmoku appears white due to the concentration of potassium at the contact surface between the substrate ceramic material and the glaze layer. In other words, as a result of the fusion of the whitish clay and a glaze rich in potassium, the glaze becomes remarkably white. It is thought that the white colour of the tenmoku tea bowls excavated from the Onada Kamashita kiln ruins is a result of this phenomenon.”

Cross sections of ash glazed white pottery (left) and Shino (right) shards. Note the whiteness of the clay in the Shiro Tenmoku body. The glazing has interacted with the clay to create a thin white layer. A white layer is also visible in the Shino body, but the ceramic material underneath is brownish.

Let us now return to the mysterious tiny black spots discussed in Part One of this article. Arakawa concludes in his book that they were the result of dust-like ash particles swirling around in the heat inside the kiln. Because the pottery was unprotected by fire clay, he writes, the particles landed on its surfaces and stuck there.

Was there another explanation? To investigate, Aoyama-sensei made one more reproduction, and gave it to the expert. For more than a decade, until 2012, the two men drank tea from the bowls every day. Over time, the aforementioned bubbles in the glazing burst one by one, and tea residue built up in the small holes they left. Little by little, these tiny black dots specked the ceramic surface in increasing numbers.

This was the final piece of the evidence. Aoyama-sensei and the professor had shown that there was a strong likelihood that the reproductions had been created using the same methods and materials as had been used for the Shiro Tenmoku listed as Very Important Cultural Assets by the government. The idea that the latter had been produced in Onada could no longer be ruled out.

Pottery used over decades or even centuries acquire a wear that becomes ever more evident as time goes by. This is why Aoyama-sensei felt the bowls must be used at least ten years. You will also note that the base of the museum owned bowls has a brown colour. This, too, is a change that has happened over time, according to Aoyama-sensei. When the bowls were new, their bases must have been white.

To prove his point, Aoyama-sensei opens a book and puts a bowl on top of a picture inside. "Take a look at the piece in the Tokugawa Art Museum in Nagoya in this book,” he says. “Now look at my reproduction bowl on top of it. You probably even have trouble telling which is which,” he says, laughing. “Note the cracks in the glazing on both pieces."

To prove his point, Aoyama-sensei opens a book and puts a bowl on top of a picture inside. "Take a look at the piece in the Tokugawa Art Museum in Nagoya in this book,” he says. “Now look at my reproduction bowl on top of it. You probably even have trouble telling which is which,” he says, laughing. “Note the cracks in the glazing on both pieces."

Note the astonishing similarity between the Tokugawa bowl and the reproduction made by Aoyama-sensei.

Many observers in Japan today recognize that by using the clay in Onada and the ash glazing practiced at the ancient kilns in the village it is possible to produce Shiro Tenmoku bowls like those listed as Important National Treasures by the government. The idea that Shiro Tenmoku - previously believed to be a form of Shino ware - is ash glazed pottery originating in Onada is gaining support.

Many observers in Japan today recognize that by using the clay in Onada and the ash glazing practiced at the ancient kilns in the village it is possible to produce Shiro Tenmoku bowls like those listed as Important National Treasures by the government. The idea that Shiro Tenmoku - previously believed to be a form of Shino ware - is ash glazed pottery originating in Onada is gaining support.

AOYAMA-SENSEI'S MESSAGE TO THE WORLD

Given the fact that the awareness of the true origin of Shiro Tenmoku has yet to reach the West, what does Aoyama hope a Western audience can learn from this?

“It is true,” he replies, “that the history of pottery in Japan has undergone a vital review over the last years. However, there are other things also worth attention. I often ask myself how pottery in Japan would have developed if the Shiro Tenmoku had never existed. Would the now so famous irregular shapes of the Momoyama pottery that came later ever have appeared on the scene? After all, Shino and Oribe pottery came into existence in the Mino region as the result of a centuries-long development preceding the Momoyama era. Now we know that Shiro Tenmoku is not Shino ware, but centrepieces of an earlier development. One that gave birth to the Mino ware renaissance and radical new designs.”

My mission in life is to understand this process. Spinning my potter’s wheel, I delve ever deeper into the mysteries of the ancient techniques. I am striving to recreate 5th century Sanage ware, a pottery with its roots in the Korean Sue ware. I try to recreate the yama chawan and ash glazed Mino ware. I am hoping to find out how the ash glazing of olden times was made.

I absorb the wisdom from the earth in Onada, always learning. Employing the knowledge and skills I acquire, I want to make new pottery for people to enjoy and use in their daily life today and in the future.

“It is true,” he replies, “that the history of pottery in Japan has undergone a vital review over the last years. However, there are other things also worth attention. I often ask myself how pottery in Japan would have developed if the Shiro Tenmoku had never existed. Would the now so famous irregular shapes of the Momoyama pottery that came later ever have appeared on the scene? After all, Shino and Oribe pottery came into existence in the Mino region as the result of a centuries-long development preceding the Momoyama era. Now we know that Shiro Tenmoku is not Shino ware, but centrepieces of an earlier development. One that gave birth to the Mino ware renaissance and radical new designs.”

My mission in life is to understand this process. Spinning my potter’s wheel, I delve ever deeper into the mysteries of the ancient techniques. I am striving to recreate 5th century Sanage ware, a pottery with its roots in the Korean Sue ware. I try to recreate the yama chawan and ash glazed Mino ware. I am hoping to find out how the ash glazing of olden times was made.

I absorb the wisdom from the earth in Onada, always learning. Employing the knowledge and skills I acquire, I want to make new pottery for people to enjoy and use in their daily life today and in the future.

Afterword

It has been an honor to record Aoyama-sensei’s thoughts and transmit them for the first time to an English speaking audience. I believe we must have visited the potter’s studio at least 15 times during this hot summer in Onada. Everytime we did, we were served mattcha tea in Shiro Tenmoku bowls that must look very much like those once owned by the medieval tea master Takeno Jōō.

Perhaps this is one of Aoyama-sensei’s greatest contributions to the world of pottery - the fact that we can drink from his bowls. For even though the pieces in the museums are worthy awe in many respects, they are not easily accessible to ordinary people. We are lucky if they are even on display when we visit. But you will be able to hold the sensei’s beautiful Shiro Tenmoku in your hands and drink from them if you pay a visit to his studio in Onada.

Isn’t that what tea bowls are for?

Hans Karlsson

Onada, Tajimi, August 28, 2018

Perhaps this is one of Aoyama-sensei’s greatest contributions to the world of pottery - the fact that we can drink from his bowls. For even though the pieces in the museums are worthy awe in many respects, they are not easily accessible to ordinary people. We are lucky if they are even on display when we visit. But you will be able to hold the sensei’s beautiful Shiro Tenmoku in your hands and drink from them if you pay a visit to his studio in Onada.

Isn’t that what tea bowls are for?

Hans Karlsson

Onada, Tajimi, August 28, 2018

Notes

- Moxa [eng: Mugwort] earth is regarded as highly suitable for making chawan. Mugwort is a common name for several species of aromatic plants in the genus Artemisia. In Japan, the fuzz on the underside of the mugwort leaves is gathered and used in moxibustion. This is a traditional Chinese medicine therapy which consists of burning dried mugwort (moxa) on particular points on the body. In Japanese pottery, the term “moxa” is used to express the lightness of “moxa earth” (see image). It is also described as having a “frogs’ eyes” quality because of the tiny Quartzite (keisa ja:珪沙) particles it contains. Moxa earth is regarded as ideal for making chawan with a rough, voluminous quality.

- Arakawa published his thoughts on Shiro Tenmoku in “Shino, Kiseto, Setoguro” (ja: 志野・黄瀬戸・瀬戸黒), Heibonsha, book 11 of 28 in the series “Nihon Tougei Taikei” (ja: 日本陶磁大系), 1989, Toyozō Arakawa ;(ja: 荒川 豊蔵 ), Junichi Takeuchi (ja:竹内 順一)

For more background, see this older story in which Aoyama-sensei discusses the developments that led to Shino and Oribe ware.