oribe - An AESTHETIC revolution

In Hyouge Mono, a 13 episode series broadcast by public service NHK, the protagonist is a retainer of Oda Nobunaga, caught between loyalty to his lord and loyalty to the art that he loves – the utensils for the Japanese tea ceremony. The first book by manga artist Yoshihiro Yamada introduce the story with the following words on the cover:

"It was the Sengoku-era, when the warlords usurped each other. There was a man who's soul was overtaken by the ways of tea and material greed, as he worked his way toward greater power and status. His name was Sasuke Furuta, a subordinate warrior of Nobunaga Oda. With his world broadened by Nobunaga the Genius, and his spiritual insight learned from Senno Soueki the Master of Tea, Sasuke drove road to Hyoge Mono. To live or not to live. For the power or the art. That is the question!!"

In the first book, in a rather bizarre development, a beleaguered opponent of Nobunaga is offered pardon in exchange for a priceless tea kettle, but instead choose to blow himself and the kettle into pieces. While the fictional event seems far-fetched, the obsession about tea utensils in these days was real. It is a trait often attributed to Furuta Oribe, on which Sasuka Furuta in the passage here above is modeled. His burning enthusiasm has survived the centuries into our time. When I met Mr. Watanabe in his Tajimi shop (you remember him from part 1, I hope?), I felt that passion still burning in him. Half of his shop was devoted to Momoyama pottery. Momoyama was in his view the golden age of ceramics in Japan. Robert Yellin brings us back to those days in his Japan Times piece "Magic of Momoyama Mino Still Shines Across the Years":

Let's take a walk back in time, say to the 1570s. Not just any ol' hike through the woods, but a pilgrimage to the birthplace of some of Japan's greatest ceramic wares.

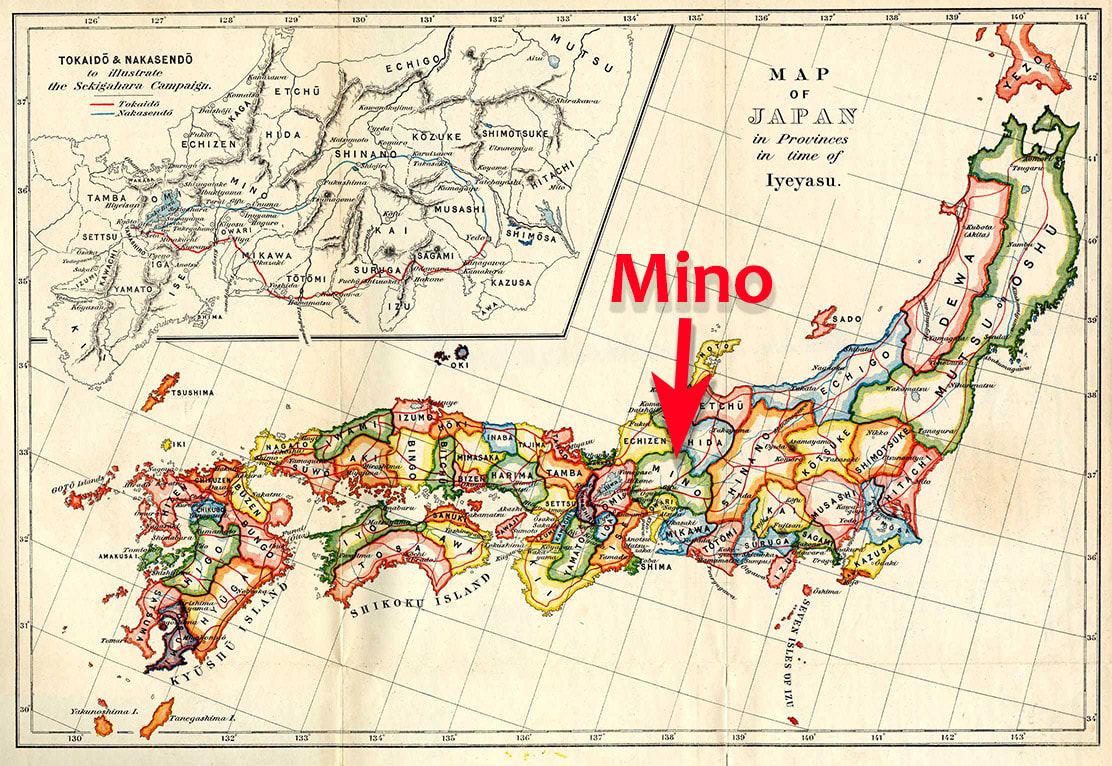

We find ourselves in the hills surrounding Toki and Tajimi cities in Mino Province, now in southern Gifu Prefecture. Many new kilns have been established by potters fleeing the frequent battlegrounds of Owari Province, where the great kilns of Seto are. Notably, one Kato Kagemitsu (1513-1585) relocated here in 1574 and opened kilns in Okaya, Ohira and Kujiri that fired some of the Shino-ware masterpieces of the Momoyama Period (1573-1615).

Shino - which we will return to later installment - is believed to have originated in Kani, which borders to Tajimi. The four Mino styles relate exclusively to the tea ceremony, and therefor also has a historical/political connection to the shaping of the Japan we know today. Kato, the pottery master, seems to have been instrumental here. As Yellin writes about Kato, the pottery master: "]...] he introduced [...] classic ceramics: Setoguro (black Seto), Ki-Seto (yellow Seto) and Oribe". This time I would like to focus on Oribe. It broke with tradition, and has a very special place in many pottery lover's hearts. And the story start with the master of tea masters, Sen no Rikyū.

an aesthetics revolutionary enter the stage

We are about to enter the 17th century, and it is soon time for our protagonist, Furuta Oribe, to rise to a new role, and he shall do so on the shoulders of a giant - Sen no Rikyū. The tea master introduced important changes of the tea ceremony, which originated in China. He loved extreme simplicity and minimalism, making use of Japanese household utensils rather than exclusive Chinese ones. The style is known as Urasenke today. The Urasenke Tankokai Federation website introduces him in the following way:

"SEN Rikyū, the 16th-century tea master who perfected the Way of Tea, was once asked to explain what this Way entails. He replied that it was a matter of observing but seven rules: Make a satisfying bowl of tea; Lay the charcoal so that the water boils efficiently; Provide a sense of coolness in the summer and warmth in the winter; Arrange the flowers as though they were in the field; Be ready ahead of time; Be prepared in case it should rain; Act with utmost consideration toward your guests.

According to the well-known story relating the dialogue between Rikyū and the questioner mentioned above, the questioner was vexed by Rikyū's reply, saying that those were simple matters that anyone could handle. To this, Rikyū responded that he would become a disciple of the person who could carry them out without fail.

This story tells us that the Way of Tea is basically concerned with activities that are a part of everyday life, yet to master these requires great cultivation. In this sense, the Way of Tea is well described as the Art of Living."

As we saw in the previous part of this series, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Rikyū's new master after the death of Oda Nobunaga, was of simple origin but like Nobunaga very much aware of the importance of the tea ceremony for political purposes. Rikyū, the tea master, was perhaps a little to close to the power game for his taste. Whatever the reason was, Hideyoshi ordered Rikyū to commit suicide by seppuku (hara-kiri).

Furuta Oribe (1544 – 1615), a warlord and Rikyū's disciple, became the foremost tea master in the land after Rikyū's death. Oribe is unique in many senses, including that he has inspired the name of one of the most famous styles of classic pottery in Japan - Oribe yaki (“Oribe ware”), denoting the type of pottery he preferred to use in his tea ceremony: a simple rustic tea bowl with an irregular shape, thick glaze, and soft monochromatic colour. Oribe's burning passion for pottery has fascinated later generations, even today. As mentioned above, he is the main character of the Hyouge Mono manga, a man in conflict between his sense of duty as a warrior and his obsession for beautiful pottery.

Oribe was born in 1544, in Mino province, and originally a retainer of Oda Nobunaga. The period starting about 20 years before and ending 20 years after the shift to the 17th century is regarded as the Golden Age of Mino ware, and Furuta is right at the centre of it. He had a strange, warped sense of beauty that has come to be associated with the irregular, bent shapes and forms of Japanese pottery around the world. It is no coincidence that the premiere shopping street for pottery in Tajimi, here in the centre of the old Mino region, is named after him.

Oribe was a daimyo, or military chief, and served as such all his adult life. It is unclear what his connection is to the birth of the Oribe style. Probably he was too busy with his duties to spend any time involving him self deep in the creative process. His interest in aesthetics covered a wide spectrum, and he was involved in garden design as well as the design of tea houses, where he also introduced new thinking.

However, even though he was probably not connected directly to the invention of the Oribe style, his meeting with the grand master of the Way of Tea in Japan, Sen no Rikyū (1522 – 1591), would prove to be of enormous importance for the aesthetics of the Japanese tea ceremony, including that of tea utensils. That is precisely the area in which Mino ware, and Oribe not the least, shines.

Oribe and Rikyū met around 1582 - the same year their master Nobunaga died - and by 1590 Oribe had become one of Rikyu's seven leading disciples. After the death of Nobunaga, both men now served under Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the most powerful war lord in the land at the time.

A warped sense of beauty

More information about the wares displayed here at the bottom of this page.

After master Rikyū's forced suicide, Oribe rose to a leading role as the designer of a new set of rules for the warrior's tea ceremony. Oribe began to move away from the austere tone Rikyū had established, and made an even stronger emphasis of the use of Japanese vessels, introducing the use of contemporary wares, which he "seems to have promoted aggressively," according to Miyeko Murase. Murase was involved in the Oribe ware display "Turning Point: Oribe and the Arts of 16th Century Japan", at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2003.

Oribe is said not just have had a taste for imperfection, but to create it if necessary, championing an revolution in the aesthetic approach to stoneware. Souren Melikian, a commentator on the Met's exhibition, notes in the article "The aesthetics of the imperfect", for the Herald Tribune:

Oribe is said not just have had a taste for imperfection, but to create it if necessary, championing an revolution in the aesthetic approach to stoneware. Souren Melikian, a commentator on the Met's exhibition, notes in the article "The aesthetics of the imperfect", for the Herald Tribune:

"A later author accounts in 1727 how Oribe broke a Korean bowl deemed too large for the tea ceremony. Having made two cuts at a right angle, he glued the fragments together with red lacquer. [...]Another time, Oribe cut a horizontal calligraphic scroll, too large to hang in his tea room in one piece. The custom spread.

[...]Oribe anticipated all that the West would struggle for three centuries later. He was the first voice of an intellectual challenging the establishment taste for orderliness."

Oribe's obsessive ways and strangeness may have cost him his life. Furthermore, Oribe's Christian connection was strong, which was dangerous in these days.

At the time, the Portuguese Jesuits were on their way to stronger influence in the country, and as they allied with various war lords who could be seen as a threat to Hideyoshi, they were a dangerous connection for Oribe. The Jesuits pursued their goals cleverly, and even they realised the importance of the tea ceremony, which they began to use as a propaganda vehicle. Ultimately, Hideyoshi grew impatient with the Christians, and had 26 of them executed by crucifixion. It was the beginning of the end of Christian influence in Japan.

Hideyoshi was violent, but Oribe would survive his master to serve under the third of the three great unifiers of Japan, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who ended the last resistance to the Tokugawa rule in the new, Edo era by sacking Hideyoshi's and the Toyotomi clan's stronghold, Osaka castle, in 1615. Oribe had initially been favoured by the Tokugawas and taught this art to the shōgun Tokugawa Hidetada, but was forced to plot in Kyoto against the Tokugawa and the Emperor, and ordered by Tokugawa to commit suicide (seppuku), along with his son.

Still, even after his suicide, Oribe's influence grew. The art of the imperfect triumphed in ceramics. You just need to visit Mr. Watanabe in his store in Tajimi to feel it.

Still, even after his suicide, Oribe's influence grew. The art of the imperfect triumphed in ceramics. You just need to visit Mr. Watanabe in his store in Tajimi to feel it.

more about oribe and mino ware

Throughout the centuries, four styles of Mino were developed that differ from each other in appearance. These have strong connections to tea ceremony:

- Ki-Seto ware: style is yellow.

- Setoguro ware: style is black.

- Shino ware: Style is often grey with autumn grasses in white as a prominent theme. This result is achieved by incising through a slip of iron oxide and covered with feldspar glaze. In the oven, the fire would bring our variations in colour through the uneven glaze. Sub-styles are Muji-Shino, E-Shino, Beni-Shino, Aka-Shino, and Nezumi-Shino.

- Oribe ware: style is green and black. Sub-styles are Ao-Oribe, So-Oribe, Aka-Oribe, Narumi-Oribe, Shino-Oribe, and Kuro-Oribe.

- Oribe ware broke from the previous, more somber tradition, introducing vivid colours and patterns.

- New technological advance in ceramics made the dramatic appearance of Oribe possible.

- The style went beyond the tea bowl. The irregular shapes were introduced also for dishes for serving food.

- Green copper glaze and bold painted designs are typical for the Oribe style.

Slide show Images in this story

(in order from left to right):

Sō-Oribe incense burner with lion shape knob, Edo period, dated 1612.

Sō-Oribe incense burner with lion shape knob, Edo period, dated 1612.

By Puchku (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Ao-Oribe square dish with bird design, stoneware with iron-oxide decoration under copper-oxide glaze, Momoyama period, c. 1573–1615.

By Daderot [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

Set of five food vessels for the tea ceremony, glazed stoneware, Momoyama period

See page for author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Ewer, glazed stoneware, Momoyama period, early 17th century

Oribeguro kutsugata chawan, early Edo period, c. 1620