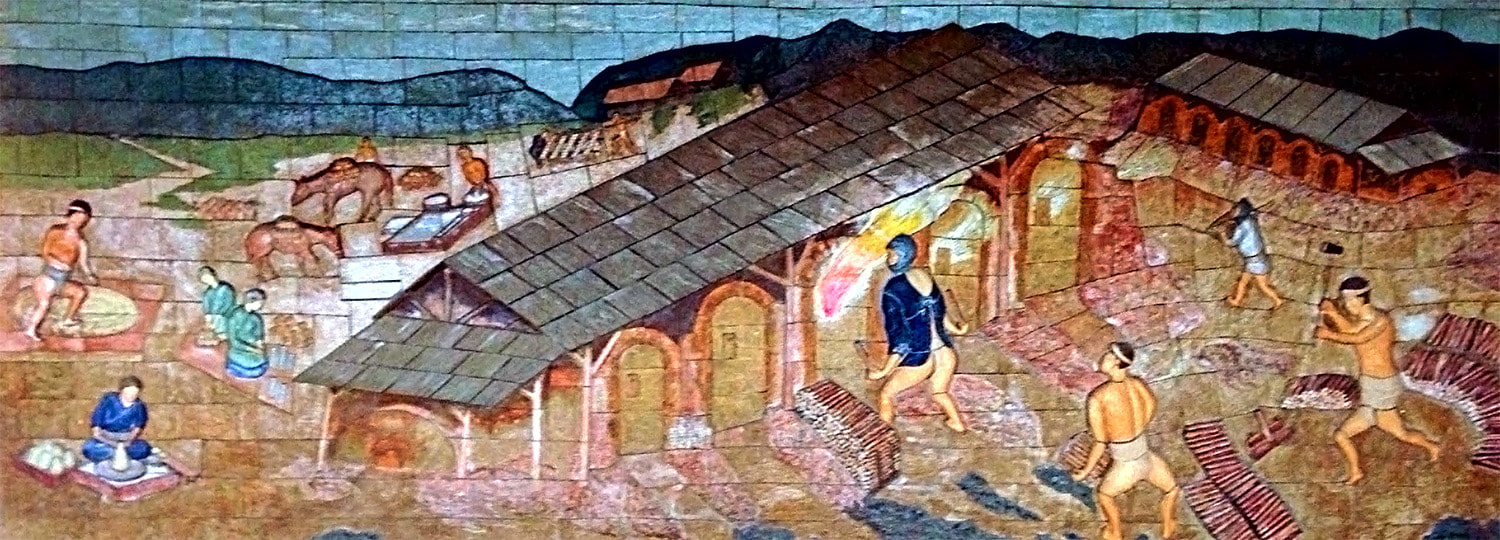

It is said that one reason for the eel becoming a local delicacy here in Tajimi is that the workers at the kilns in the area needed food with high energy value to keep them going during their long shifts. They had to endure the terrible heat from the inferno going on in the firing chambers and long shifts looking after the kiln to avoid a disastrous failed firing.

This mural depicts what the workplaces looked like when the pottery industry began to take off in the region in the shift between the 16th and 17th centuries. People were much the same then as they are today, and there were probably the same kind of episodes going on then as we know from stories from later eras. If you look at the design of the so called ascending kilns, they consist of many chambers, and each chamber required a separate firing. There was thus a break between each firing, and each successful firing was often celebrated with a drinking party. It is said that many a worker have been scolded for oversleeping the next shift after one of those bouts.

Like many other aspects of Japanese culture, the know-how necessary for kiln building was imported from China via the Korean peninsula. Kilns have developed over thousands of years, but particularly famous in Japan are the noborigama (the climbing kiln), and its predecessors the anagama and the ogama (large kiln). Each stage in the development of kiln technology made possible new production methods, better efficiency and higher quality products.

a kiln to satisfy the hunger for oribe ware

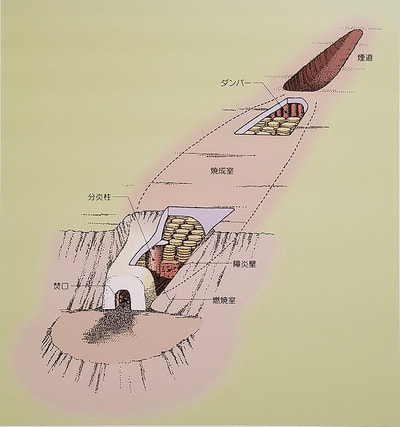

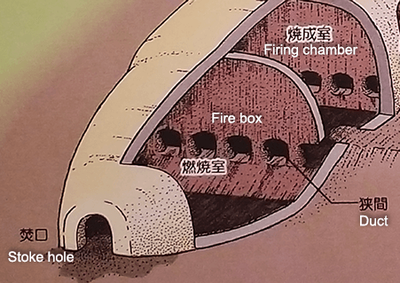

The anagama was introduced to Japan from the Korean peninsula in the first half of the 5th century, and took advantage of the terrain to make it possible to fire more wares at a time. By building the kiln in a slope and placing the firebox at the bottom, the flame and hot gases were forced to pass through the wares stuffed in the long, rising chamber before they left via a damper through an exhaust opening.

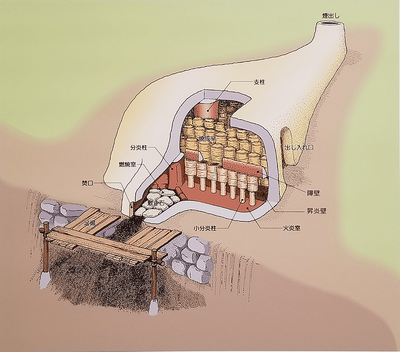

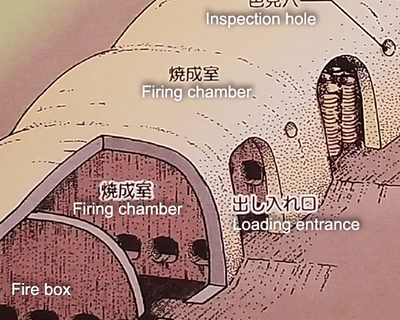

With the ogama (large kiln) efficiency was further improved by building the kiln above ground. The size of the firing chamber could be increased and it could be loaded from the side, among other improvements.

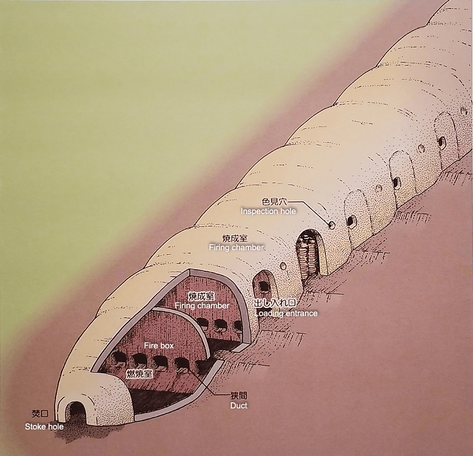

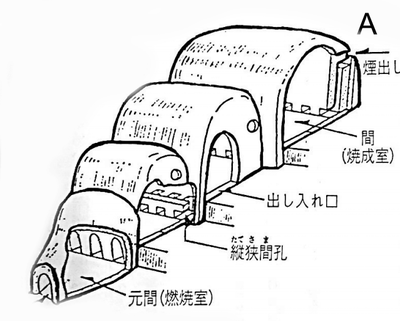

But it is really the noborigama - the "climbing" or ascending kiln - that has been equated with the rapid development of the ceramics industry in Japan and the Mino region after these earlier technological breakthroughs. According to historical records, a potter by the name of Kato Kagenobu brought the technology from Kyushu in southern Japan to the city of Toki in 1605. Toki, a neighboring city to Tajimi, became the springboard for the large scale production of oribe ware in the Mino region until around the mid 1620's. The efficiency of noborigama made this enterprise possible. By partitioning the kiln into a long chain of smaller firing chambers the energy efficiency was hugely improved, and large volumes could now be produced to satisfy the growing demand for oribe ware from the market. Oribe was a sensational style, much different from anything seen before, and became the preferred aesthetic for tea ceremony utensils, which was very fashionable at the time.

With the ogama (large kiln) efficiency was further improved by building the kiln above ground. The size of the firing chamber could be increased and it could be loaded from the side, among other improvements.

But it is really the noborigama - the "climbing" or ascending kiln - that has been equated with the rapid development of the ceramics industry in Japan and the Mino region after these earlier technological breakthroughs. According to historical records, a potter by the name of Kato Kagenobu brought the technology from Kyushu in southern Japan to the city of Toki in 1605. Toki, a neighboring city to Tajimi, became the springboard for the large scale production of oribe ware in the Mino region until around the mid 1620's. The efficiency of noborigama made this enterprise possible. By partitioning the kiln into a long chain of smaller firing chambers the energy efficiency was hugely improved, and large volumes could now be produced to satisfy the growing demand for oribe ware from the market. Oribe was a sensational style, much different from anything seen before, and became the preferred aesthetic for tea ceremony utensils, which was very fashionable at the time.

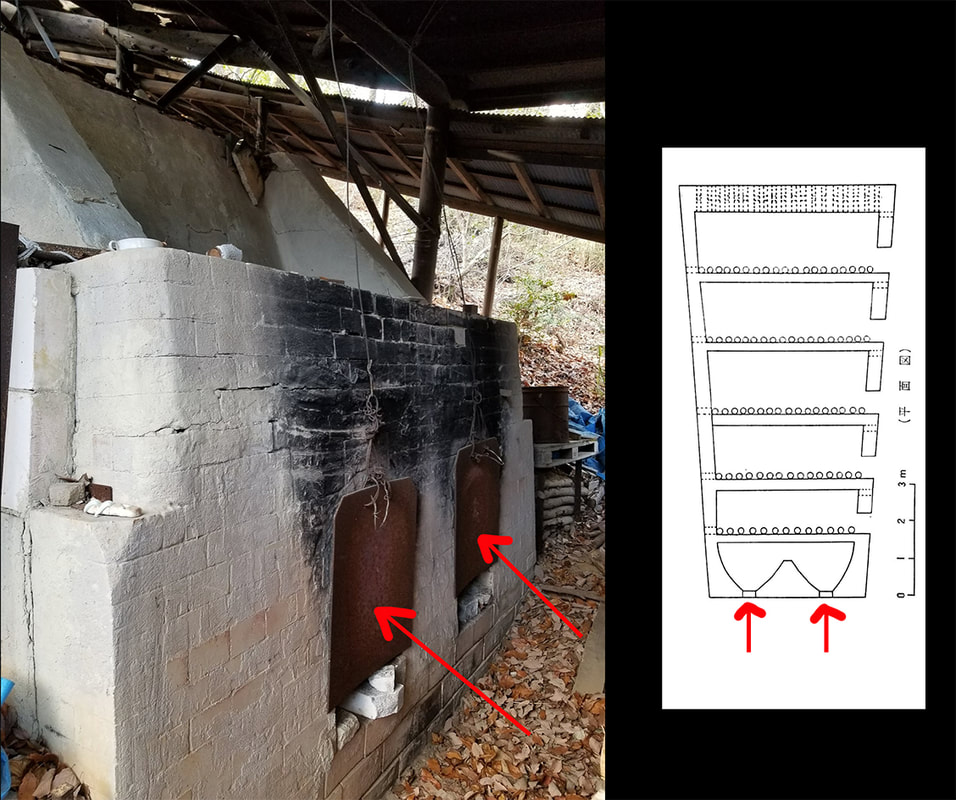

The noborigama, as well as its predecessors the anagama and the ogama, were downdraft kilns. The flame begins in a firebox at the front and travel into the first firing chamber, up over the ware - hundreds of items placed on shelves - and then back down again through the ware. Since the next fire chamber sits one step higher up in the hill so to speak, the heat finds its way through the ducts in its wall and repeats the process there. But this waste heat is not enough to finish the process, so workers must add more firewood through the loading opening on the side of the chamber.

When that firing is done, the process can be repeated in chamber number three, which has been heated from the firings of the previous chambers, and so on. At the highest level in the noborigama the flame is exhausted into an underfloor chamber and from there is drawn up the chimney.

All this saves time and firewood, which was important, because the whole process took weeks, sometimes a month or more. Large noborigama can fire a hundred thousand wares or more. That means an awful lot of firewood to be fed to the flames and goods to be loaded and unloaded, all in that terrible heat. It's not hard to see why the workers needed eel and drink to keep going.

When that firing is done, the process can be repeated in chamber number three, which has been heated from the firings of the previous chambers, and so on. At the highest level in the noborigama the flame is exhausted into an underfloor chamber and from there is drawn up the chimney.

All this saves time and firewood, which was important, because the whole process took weeks, sometimes a month or more. Large noborigama can fire a hundred thousand wares or more. That means an awful lot of firewood to be fed to the flames and goods to be loaded and unloaded, all in that terrible heat. It's not hard to see why the workers needed eel and drink to keep going.

While the wood kilns eventually came to be largely replaced with coal based ones and later gas and electricity kilns, potters still love and use them both in Japan and abroad. As Richard Zakin writes in the article "Kilns and Kiln Designs (1):

High-temperature wood firing is still used today by ceramists who value the richness of its wood ash, flashing, and reduction effects. During the firing the ashes of the wood fuel fall naturally upon the ware, and if the firing temperature is high enough the ashes are volatilized and become a glaze.

These glazes have a soft dappled imagery which covers the top surfaces of the piece and falls gently away toward the foot of the piece. The richness of these surfaces is the main argument for using wood as a high-fire fuel.

Oribe was only the beginning

The noborigama would continue to play a huge role in the devolopment of the Japanese ceramics industry until the 1900's. We will complement this article with the later part of this story in an upcoming article.

The story is not over yet, however. We hope that more foreigners will discover the fun of pottery through the world of the noborigama. We are presently working on a film project to present the story of Mino ware in Tajimi in Virtual Reality to make it an experience accessible to anyone with an Internet connection. A noborigama will be featured in that film. We also hope that foreign visitors will be able to participate in a firing of the large noborigama at The VOICE workshop here in Tajimi. It is not often used due to the large volumes of wares necessary to justify a firing, but it does happen on occasion, and it would be fantastic if many foreigners could participate in such an event.

Sources

Books

Various material from the Tajimi City Library, further details will be provided shortly.

Articles

Richard Zakin, "Kilns and Kiln Designs, in the booklet "A Guide to Ceramic Kilns", published by ceramicartsdaily.org

Exhibitions

Text material from the permanent exhibition at the Minoyaki Museum, Tajimi.

Images

Illustrations of the anagama kiln, ogama kiln, and noborigama kiln kindly provided by Minoyaki Museum, Tajimi.

The photographs of the Shino ware bowl and the Oribe tea bowl were also made possibly by the co-operation of the Minoyaki Museum, Tajimi.