the ceremony

By Hans Karlsson

This is the second installment of two of this article. You can find the first installment here.

As I mentioned in Part One of this article, according to the traditional East Asian Zodiac this is going to be an unlucky year for me. The mysterious ceremony I so busily helped preparing for would turn out to be an event related to the Eastern calendar. Of this I had no idea at this point. I just tried my best to be helpful, carrying offerings to the little altar in the back of the shrine, pouring sake in small cups, and scurrying about trying to look busy.

People began to arrive to the little shrine, climbing the steep chairs up the hill side. The men were dressed in formal suits and the ladies in fine dresses. There was a young girl who arrived wearing a school uniform. Most of the participants seemed to be in their 60s, but there were some younger men, and this one young girl. They washed their hands outside the shrine, as is the custom in the Shinto tradition. Then they climbed the stair case leading into the shrine and sat down on the small collapsible chairs we had arranged inside in neat lines. People were chit-chatting, apparently waiting for something to happen. I retreated with the rest of our little support team to the back of the room.

Now the chattering quieted down as a man who was apparently to conduct the ceremony stepped into the hall. It was a kannushi - a "god master" wearing the typical ebōshi hat and the beautiful dress of a Shinto priest. He was holding an ōnusa wand decorated with white paper streamers in his hand.

People began to arrive to the little shrine, climbing the steep chairs up the hill side. The men were dressed in formal suits and the ladies in fine dresses. There was a young girl who arrived wearing a school uniform. Most of the participants seemed to be in their 60s, but there were some younger men, and this one young girl. They washed their hands outside the shrine, as is the custom in the Shinto tradition. Then they climbed the stair case leading into the shrine and sat down on the small collapsible chairs we had arranged inside in neat lines. People were chit-chatting, apparently waiting for something to happen. I retreated with the rest of our little support team to the back of the room.

Now the chattering quieted down as a man who was apparently to conduct the ceremony stepped into the hall. It was a kannushi - a "god master" wearing the typical ebōshi hat and the beautiful dress of a Shinto priest. He was holding an ōnusa wand decorated with white paper streamers in his hand.

Like everyone else in the hall he was wearing slippers (wearing shoes inside is taboo in Japan, not only in holy places but private homes as well). He strode across the wooden floor and stopped next to the exit leading to the little altar behind the main building where we had placed the offerings.

The kannushi began a lengthy chant of holy words I could not understand much of, except a phrase here and there, waving his wand, apparently addressing the deity of the shrine. If you are not familiar with Shinto, it is the native religion of Japan, stemming from a collection of native beliefs and mythology. It is a belief system devoted to 'spirits' (kami), who can be ancestors or beings dwelling in nature. That is why its shrines, like the one in our local community here in Onada, are built in natural environments such as the forest that climbs up the hillside of our White Mountain.

Finally the kannushi was done and turned to his audience. "We will begin calling your names in a moment," he said the in a deep and priestly voice. "We will not read your addresses, however, as it would drag out the ceremony too long."

Everybody listened attentively to the priest, but I had already begun to lose my focus. The sharp back edges of my too small, borrowed slippers dug into my foot soles. I tried to shift my weight a bit too ease the pain. Maybe I should just step out of the darn things? Unfortunately I was also aware of how ice-cold the floor was after trying to skip the tiny slippers in the beginning of our preparations. The hall had no windows and was literally as cold as it was outside. People were wearing thick winter clothes. Some of them taken off their thick jackets to look more properly dressed for the ceremony, but they looked like they were having regrets. I decided to endure the pain in my feet and try to find as comfortable as posture as I could, hoping it wouldn't take to long for all of this to end. Not knowing why on earth we were all doing this was annoying, yet at the same time I was curious about what was going to happen. It helped dull the pain in my feet to some degree.

Now that the priest's chanting was over everything was quite in the little hall. You could hear a pin drop. What was going to happen next? Suddenly an electronic melody broke the silence, and everyone turned their eyes to me. I felt a vibration at my chest. My damn phone! Everyone giggled as I tried to pull out the phone and stop the ringing. Unfortunately I hadn't quite figured out how to do that very quickly, as I was still not familiar with its functions.

"Don't worry one of the men in the support team whispered in my ear. Go outside and take the call."

That seemed to be quite a rude thing to do, so I kept on struggling until I managed to stop the ringing, but only after logging in first.

The kannushi gave me a stern look. I bowed awkwardly to apologise, when the melody started playing again. More giggles as I struggled to log in once more and stop the thing. This time I managed to do it slightly faster, and pressed the power button to power down the handset. I wished there was a hole in the floor so I could climb down and hide. Fortunately nobody seemed be be upset, including the priest.

Now a man standing next to the main entrance pulled out a long piece of paper and, reading from it, called a name. A man in the audience stood up and walked over to the priest, stopped in front of him and bowed. The priest waved his wand above his head, streamers flying in the air, apparently giving the man a blessing. He handed a small tree branch with pretty, green leaves to the man who bowed again and walked into the exit to the little altar. He returned in a moment and sat down, whereupon a new name was called.

This continued until all the people in the hall had received their blessings and performed their act - whatever it was - at the altar. Now it was our turn. "Here, Hans," one man in the team said to me, and handed over a tray full of little cups of sake. "Serve everyone a cup." I began walking along the lines of people seated in the hall, serving them the alcohol. I wasn't sure how to perform this properly, so I made a little bow and held up the tray in front of them so they could take a cup. There was only a mouthful or two in the cups, just to provide the spiritual essence I suppose. Indeed, for many centuries, it is said , "Japan’s famously delicate national spirit, served in ritualistic fashion to emperors, warriors and Shinto gods, was created from rice and the spit of virgins" (2). Next I was given another brick with dried squid, and did a round with that too. Dried squid is a popular snack in pubs and bars here in Japan, but I have never been a fan of the stuff, even after thirty years in the country. When two of the young men turned down my offer I noted with satisfaction that I am not alone, careful of course to keep a straight face given the spiritual circumstances.

All the devotees received an amulet, a piece of paper inscribed with beautiful calligraphy. After these final rites the whole thing was over, and people began to leave. The priest gathered his things. Big and white like a polar bear and the crowd of black-haired, rather small people I caught his attention, and he offered me an amulet from his surplus stock. As an extra bonus one of my fellow staff members brought me a cup and filled it up from a sake bottle which still was half full. From now on things would take a turn for the better. The sun had begun to feel warmer. It was a beautiful day, in fact. The sake tasted wonderful. I stepped out of my torturous slippers and eagerly began to help collecting the chairs and mats, putting them back in their storage spaces again.

The kannushi began a lengthy chant of holy words I could not understand much of, except a phrase here and there, waving his wand, apparently addressing the deity of the shrine. If you are not familiar with Shinto, it is the native religion of Japan, stemming from a collection of native beliefs and mythology. It is a belief system devoted to 'spirits' (kami), who can be ancestors or beings dwelling in nature. That is why its shrines, like the one in our local community here in Onada, are built in natural environments such as the forest that climbs up the hillside of our White Mountain.

Finally the kannushi was done and turned to his audience. "We will begin calling your names in a moment," he said the in a deep and priestly voice. "We will not read your addresses, however, as it would drag out the ceremony too long."

Everybody listened attentively to the priest, but I had already begun to lose my focus. The sharp back edges of my too small, borrowed slippers dug into my foot soles. I tried to shift my weight a bit too ease the pain. Maybe I should just step out of the darn things? Unfortunately I was also aware of how ice-cold the floor was after trying to skip the tiny slippers in the beginning of our preparations. The hall had no windows and was literally as cold as it was outside. People were wearing thick winter clothes. Some of them taken off their thick jackets to look more properly dressed for the ceremony, but they looked like they were having regrets. I decided to endure the pain in my feet and try to find as comfortable as posture as I could, hoping it wouldn't take to long for all of this to end. Not knowing why on earth we were all doing this was annoying, yet at the same time I was curious about what was going to happen. It helped dull the pain in my feet to some degree.

Now that the priest's chanting was over everything was quite in the little hall. You could hear a pin drop. What was going to happen next? Suddenly an electronic melody broke the silence, and everyone turned their eyes to me. I felt a vibration at my chest. My damn phone! Everyone giggled as I tried to pull out the phone and stop the ringing. Unfortunately I hadn't quite figured out how to do that very quickly, as I was still not familiar with its functions.

"Don't worry one of the men in the support team whispered in my ear. Go outside and take the call."

That seemed to be quite a rude thing to do, so I kept on struggling until I managed to stop the ringing, but only after logging in first.

The kannushi gave me a stern look. I bowed awkwardly to apologise, when the melody started playing again. More giggles as I struggled to log in once more and stop the thing. This time I managed to do it slightly faster, and pressed the power button to power down the handset. I wished there was a hole in the floor so I could climb down and hide. Fortunately nobody seemed be be upset, including the priest.

Now a man standing next to the main entrance pulled out a long piece of paper and, reading from it, called a name. A man in the audience stood up and walked over to the priest, stopped in front of him and bowed. The priest waved his wand above his head, streamers flying in the air, apparently giving the man a blessing. He handed a small tree branch with pretty, green leaves to the man who bowed again and walked into the exit to the little altar. He returned in a moment and sat down, whereupon a new name was called.

This continued until all the people in the hall had received their blessings and performed their act - whatever it was - at the altar. Now it was our turn. "Here, Hans," one man in the team said to me, and handed over a tray full of little cups of sake. "Serve everyone a cup." I began walking along the lines of people seated in the hall, serving them the alcohol. I wasn't sure how to perform this properly, so I made a little bow and held up the tray in front of them so they could take a cup. There was only a mouthful or two in the cups, just to provide the spiritual essence I suppose. Indeed, for many centuries, it is said , "Japan’s famously delicate national spirit, served in ritualistic fashion to emperors, warriors and Shinto gods, was created from rice and the spit of virgins" (2). Next I was given another brick with dried squid, and did a round with that too. Dried squid is a popular snack in pubs and bars here in Japan, but I have never been a fan of the stuff, even after thirty years in the country. When two of the young men turned down my offer I noted with satisfaction that I am not alone, careful of course to keep a straight face given the spiritual circumstances.

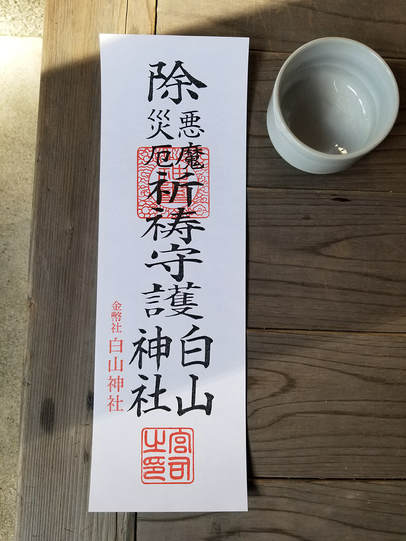

All the devotees received an amulet, a piece of paper inscribed with beautiful calligraphy. After these final rites the whole thing was over, and people began to leave. The priest gathered his things. Big and white like a polar bear and the crowd of black-haired, rather small people I caught his attention, and he offered me an amulet from his surplus stock. As an extra bonus one of my fellow staff members brought me a cup and filled it up from a sake bottle which still was half full. From now on things would take a turn for the better. The sun had begun to feel warmer. It was a beautiful day, in fact. The sake tasted wonderful. I stepped out of my torturous slippers and eagerly began to help collecting the chairs and mats, putting them back in their storage spaces again.

A happy ending

Soon we had finished our duties and stepped out from the hall into the grounds in front of the shrine. I took a closer look at my amulet. Studying its inscription I realised this must have something to do with the Eastern calendar. There was the name of the shrine at the bottom: "Hakusan Jinja" - the Shrine of the White Mountain. At the top there was a large character meaning "avoid", and underneath the characters for "evil", another roughly meaning "evil spirit", a third one meaning "calamity". And then there was this fourth character - 厄- which forms the first part of the word yakudoshi (厄年), meaning "unlucky year."

Finally it dawned on me. "Avoiding the unlucky year" was what all this had been about! This whole thing had been a ceremony to protect people born in a year that will bring bad luck or big challenges for the person of a certain age. When the a person reach that age (25, 42 and 61 for men, and 19, 33 and 37 for women) they visit their local shrine to buy lucky charms in the hope they can get through the period without a major tragedy. So this must be the year that that young girl in school uniform turns 19, the middle aged women 33 or 37, and the men 25, 42 and 61 respectively. And while they all had payed money for their amulets, I got one for free - a free ride in a sense, because I too, come to think of it, was had reached a sensitive age this year. It may all seem a bit confusing, but it's not that difficult to understand once you know how the system works. While I am turning 59 this year according to Western counting, I am in fact going to be 60 according to Japanese tradition (see "Fun Facts" here below). 60 may not be as as unlucky an age as 61, but it is close. The year preceding the yakudoshi and the one following it are also considered to be times for extra caution.

Not only had I received an amulet to keep me safe as I enter a phase of danger in my life, but I also got to taste the sweet drops of the blessed sake. The priest had left the half emptied bottle as well, and now our little team gathered around the warm fire to share it and ripe our reward for our efforts. We had a good chat, taking turns to fill up our cups emptying the bottle in the pretty February morning. The sake felt warm in my belly, my cold feet felt equally warm from the heat of the fire, and my spirit lifted as we laughed and shared the blessed rice wine to keep us safe another year. Particularly myself, as I am presently in the danger zone.

Not is this supposedly a potentially bad time for me. I am apparently also nearing the end of my time in a sense. Why? 60 is the age when you have reached full circle of your life cycle according to Eastern tradition. Considering that, I feel pretty good and ready to charge my batteries for the next round. Risking to draw divine anger for my hubris, I don't think the evil spirits will stand much chance to take me down for a while, even though I am supposed to head for rough waters. Our little morning ceremony helped me convince me of that. After all, it had an unexpectedly pleasant ending, in spite of all the Yakudoshi signs that said otherwise.

Finally it dawned on me. "Avoiding the unlucky year" was what all this had been about! This whole thing had been a ceremony to protect people born in a year that will bring bad luck or big challenges for the person of a certain age. When the a person reach that age (25, 42 and 61 for men, and 19, 33 and 37 for women) they visit their local shrine to buy lucky charms in the hope they can get through the period without a major tragedy. So this must be the year that that young girl in school uniform turns 19, the middle aged women 33 or 37, and the men 25, 42 and 61 respectively. And while they all had payed money for their amulets, I got one for free - a free ride in a sense, because I too, come to think of it, was had reached a sensitive age this year. It may all seem a bit confusing, but it's not that difficult to understand once you know how the system works. While I am turning 59 this year according to Western counting, I am in fact going to be 60 according to Japanese tradition (see "Fun Facts" here below). 60 may not be as as unlucky an age as 61, but it is close. The year preceding the yakudoshi and the one following it are also considered to be times for extra caution.

Not only had I received an amulet to keep me safe as I enter a phase of danger in my life, but I also got to taste the sweet drops of the blessed sake. The priest had left the half emptied bottle as well, and now our little team gathered around the warm fire to share it and ripe our reward for our efforts. We had a good chat, taking turns to fill up our cups emptying the bottle in the pretty February morning. The sake felt warm in my belly, my cold feet felt equally warm from the heat of the fire, and my spirit lifted as we laughed and shared the blessed rice wine to keep us safe another year. Particularly myself, as I am presently in the danger zone.

Not is this supposedly a potentially bad time for me. I am apparently also nearing the end of my time in a sense. Why? 60 is the age when you have reached full circle of your life cycle according to Eastern tradition. Considering that, I feel pretty good and ready to charge my batteries for the next round. Risking to draw divine anger for my hubris, I don't think the evil spirits will stand much chance to take me down for a while, even though I am supposed to head for rough waters. Our little morning ceremony helped me convince me of that. After all, it had an unexpectedly pleasant ending, in spite of all the Yakudoshi signs that said otherwise.

fun facts about yakudoshi

Yakudoshi ages

Women |

19 |

33 |

37 |

Men |

25 |

42 |

61 |

If you are a woman and turning 19, 33 or 37 the year you are reading this, or a man turning 25, 42 or 61, you may be in for trouble according to Japanese tradition. The ages of which years are particularly unlucky ones for women are 33 for women and 42 for men respectively. Additionally, the years immediately preceding and following the so called yakudoshi, or "misfortunous year" in the table can bring minor trouble. In other words, if you are a man turning 42 this year, you may be in for big trouble, but if you are turning 41 or 43 you still need to be careful.

Traditionally in Japan, you turn one year older when you are born. Then you turn one year older again on the first day of next year (kazoedoshi or "counting year"). Unfortunately for me I turn 59 according to the Western way of counting this year (or in the 34th year of the reign of Emperor Showa), but 60 according to the East Asian Age reckoning. That is one year ahead of my last yakudoshi in this life (61), so this year could bring trouble. Or is this so?

If you were born between February 18, 1958 and February 7, 1959, you are born in the year of the dog according to the Chinese lunar calendar. If you were born on March 28 of the same year, as was this writer, you are born in the year of the boar. That year lasted until January 17, 1960. Japan switched from the lunar year calendar to the Gregorian one in 1873, however, so now everyone born in 1959 is a boar here. How boring :-)

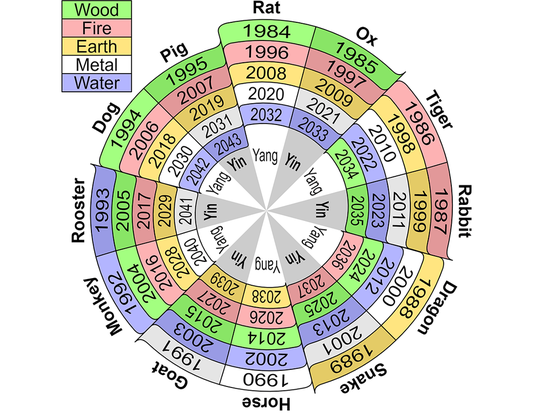

The yakudoshi has nothing to do do with the animals of the Chinese zodiac, so it is not considered better or worse to "be" a rat, dog or boar. It is thought to be related to the ideas of yin and yang, however, and the Five Elements, that are traditionally considered to be related to the years of the Chinese lunar year cycle.

While the word yakudoshi is written "unlucky" (厄) and "year" (年) in Japanese, there was also the notion that at the "worst" ages of all for a man for example (42) he is at a critical juncture in life as his combined social, physical and mental powers are near their peak. He is ripe to make his mark in society and to take on the heaviest responsibilities. In other words, things may go awfully wrong if you are not careful.

Taking a closer look at the yakudoshi and considering the ages of people in a time when the life span was much shorter, these biological ages seem to coincide with important stages in a human's life - becoming an adult, becoming a mother, attaining the peak year of one's life etc. Life expectancy at birth in 18th-century Edo Japan was according to one source (see footnote 1) around 41 years for males. But that counts all the children that died at young age, so perhaps 42 was about the peak year for male adults that survived the early years of their lives. 60 is seen as the year people have lived one full life cycle, and is celebrated even today as kanreki. This is the year when one has accomplished a full life - so to speak - and return to the beginning of the traditional 60-year lunar calendar cycle.

Taking a closer look at the yakudoshi and considering the ages of people in a time when the life span was much shorter, these biological ages seem to coincide with important stages in a human's life - becoming an adult, becoming a mother, attaining the peak year of one's life etc. Life expectancy at birth in 18th-century Edo Japan was according to one source (see footnote 1) around 41 years for males. But that counts all the children that died at young age, so perhaps 42 was about the peak year for male adults that survived the early years of their lives. 60 is seen as the year people have lived one full life cycle, and is celebrated even today as kanreki. This is the year when one has accomplished a full life - so to speak - and return to the beginning of the traditional 60-year lunar calendar cycle.

your age and zodaic character according to tradition

On the right side you will find the traditional names of each animal designated to symbolise the years of the 12 year long sexagenary cycle, which is in turn based on Jupiter's orbit of the Sun, which it completes in roughly 12 years (11.86 years to be precise). The names of the animals in the sexagenary cycle listed here are the Japanese readings of the single Chinese character for each animal. They are still used in everyday's conversation among the elderly generation, although it is more common to use the standard Japanese names for snake (hebi), rabbit (usagi) and boar (inoshishi). Terms from the sexedecimal cycle are also used for indicating rankings, as for academic grades, or for distinguishing parties in a contract.

| Birth year | Full years old | Kazoedoshi | Sexagenary cycle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heisei 30 (2018) | 0 | 1 | Inu (dog) |

| Heisei 29 (2017) | 1 | 2 | Tori (rooster) |

| Heisei 28 (2016) | 2 | 3 | Saru (monkey) |

| Heisei 27 (2015) | 3 | 4 | Hitsuji (goat) |

| Heisei 26 (2014) | 4 | 5 | Uma (horse) |

| Heisei 25 (2013) | 5 | 6 | Mi (snake) |

| Heisei 24 (2012) | 6 | 7 | Tatsu (dragon) |

| Heisei 23 (2011) | 7 | 8 | U (rabbit) |

| Heisei 22 (2010) | 8 | 9 | Tora (tiger) |

| Heisei 21 (2009) | 9 | 10 | Ushi (Ox) |

| Heisei 20 (2008) | 10 | 11 | Ne (rat) |

| Heisei 19 (2007) | 11 | 12 | I (boar) |

| Heisei 18 (2006) | 12 | 13 | Inu |

| Heisei 17 (2005) | 13 | 14 | Tori |

| Heisei 16 (2004) | 14 | 15 | Saru |

| Heisei 15 (2003) | 15 | 16 | Hitsuji |

| Heisei 14 (2002) | 16 | 17 | Uma |

| Heisei 13 (2001) | 17 | 18 | Mi |

| Heisei 12 (2000) | 18 | 19 | Tatsu |

| Heisei 11 (1999) | 19 | 20 | U |

| Heisei 10 (1998) | 20 | 21 | Tora |

| Heisei 9 (1997) | 21 | 22 | Ushi |

| Heisei 8 (1996) | 22 | 23 | Ne |

| Heisei 7 (1995) | 23 | 24 | I |

| Heisei 6 (1994) | 24 | 25 | Inu |

| Heisei 5 (1993) | 25 | 26 | Tori |

| Heisei 4 (1992) | 26 | 27 | Saru |

| Heisei 3 (1991) | 27 | 28 | Hitsuji |

| Heisei 2 (1990) | 28 | 29 | Uma |

| Heisei 1 (1989)(1/8~)Showa 64(~1/7) | 29 | 30 | Mi |

| Showa 63 (1988) | 30 | 31 | Tatsu |

| Showa 62 (1987) | 31 | 32 | U |

| Showa 61 (1986) | 32 | 33 | Tora |

| Showa 60 (1985) | 33 | 34 | Ushi |

| Showa 59 (1984) | 34 | 35 | Ne |

| Showa 58 (1983) | 35 | 36 | I |

| Showa 57 (1982) | 36 | 37 | Inu |

| Showa 56 (1981) | 37 | 38 | Tori |

| Showa 55 (1980) | 38 | 39 | Saru |

| Showa 54 (1979) | 39 | 40 | Hitsuji |

| Showa 53 (1978) | 40 | 41 | Uma |

| Showa 52 (1977) | 41 | 42 | Mi |

| Showa 51 (1976) | 42 | 43 | Tatsu |

| Showa 50 (1975) | 43 | 44 | U |

| Showa 49 (1974) | 44 | 45 | Tora |

| Showa 48 (1973) | 45 | 46 | Ushi |

| Showa 47 (1972) | 46 | 47 | Ne |

| Showa 46 (1971) | 47 | 48 | I |

| Showa 45 (1970) | 48 | 49 | Inu |

| Showa 44 (1969) | 49 | 50 | Tori |

| Showa 43 (1968) | 50 | 51 | Saru |

| Showa 42 (1967) | 51 | 52 | Hitsuji |

| Showa 41 (1966) | 52 | 53 | Uma |

| Showa 40 (1965) | 53 | 54 | Mi |

| Showa 39 (1964) | 54 | 55 | Tatsu |

| Showa 38 (1963) | 55 | 56 | U |

| Showa 37 (1962) | 56 | 57 | Tora |

| Showa 36 (1961) | 57 | 58 | Ushi |

| Showa 35 (1960) | 58 | 59 | Ne |

| Showa 34 (1959) | 59 | 60 | I |

| Showa 33 (1958) | 60 | 61 | Inu |

| Showa 32 (1957) | 61 | 62 | Tori |

| Showa 31 (1956) | 62 | 63 | Saru |

| Showa 30 (1955) | 63 | 64 | Hitsuji |

| Showa 29 (1954) | 64 | 65 | Uma |

| Showa 28 (1953) | 65 | 66 | Mi |

| Showa 27 (1952) | 66 | 67 | Tatsu |

| Showa 26 (1951) | 67 | 68 | U |

| Showa 25 (1950) | 68 | 69 | Tora |

| Showa 24 (1949) | 69 | 70 | Ushi |

| Showa 23 (1948) | 70 | 71 | Ne |

| Showa 22 (1947) | 71 | 72 | I |

| Showa 21 (1946) | 72 | 73 | Inu |

| Showa 20 (1945) | 73 | 74 | Tori |

| Showa 19 (1944) | 74 | 75 | Saru |

| Showa 18 (1943) | 75 | 76 | Hitsuji |

footnotes

1) Pomeranz, Kenneth (2000), The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy, Princeton University Press, p. 37, ISBN 978-0-691-09010-8

2) "Almost seven thousand years ago, a bored or hungry peasant popped a grain of rice in her mouth and noted, as she chewed, an increasing sensation of sweetness: saliva, it turns out, contains an enzyme able to break down rice starch into glucose. How she got around to fermenting the soggy remains of her prehistoric chewing gum I have no idea, but her descendants took to the results with enthusiasm, allocating unmarried girls to help create bijinshu, or 'beautiful woman sake'." From "Sake: a spirit made from the spit of ancient virgins, article by Nina Caplan in The Statesman.

images

Shinto Priest