A visit to Uoseki

If you have the slightest interest in food and plan to visit Tajimi, a visit to an unagiya - an eel restaurant - is a must. This writer was never a fan of eel before moving here, partly because my mother had always told me it is a fatty food. I didn't visit an unagiya even once during my years in Tokyo. But here in Tajimi, I was soon invited to my first treat, and it was an eye-opener. Since then I have become something of an eel fan. For this article, I had the opportunity to interview Mr Hiroyuki Murate, the chef and owner of Uoseki, one of the most popular eel restaurants among foreign visitors to Tajimi.

"In a way, it is a mixed blessing for me," says Mr Murate, "because I don't speak foreign languages. Still, we are delighted to see a quickly growing number of foreign customers. Some come in groups; some are lone travelers, many from Taiwan. Many of them come travelling alone, and many are female. They must have read about us on some blog on the Net."

Only a small trickle of the information on travel and food in Japan finds its way to a foreign audience. Very little of the total flow is available in English.

Here is how a Japanese food blogger describes his visit to an eel restaurant in Tajimi:

Here is how a Japanese food blogger describes his visit to an eel restaurant in Tajimi:

People often speak of eel in Japan as one of two styles: Kansai or Kanto. I enjoy it either way. I think it is mostly a matter of how good the cook is. In Tajimi I was happy to find the tare (dipping sauce) to be delicious and not too sweet. One could argue the taste will appeal to the male gourmet. Eel is often sweet and heavy, but here it was different. It was easy on the stomach - eel for adults, if I may say so. And there was this crispiness to it that I truly enjoyed! Tajimi has many eel restaurants, some elegant and classy and some rustic and unique. It is a city where a century-long tradition still thrives, and I was happy to discover a taste I believe people here have enjoyed since the olden days.

Mr Murate spent many years working in a famous restaurant in Tokyo's Ginza district. Why did he decide to return here? "I thought it would be a shame if the family business would end after a century," he explains. "I was the only one who could continue. So it was that in mind I went to Tokyo to learn from the best. My goal was to return and continue our old family business. My sister had married so I was the only one who could do it." While this is a business that goes many generations back in Mr Murate's family, the custom of eating eel in Japan is older still. It goes all the way back to prehistory.

eel as a culinary tradition

There are two main eel cooking traditions in Japan, one in the West (Kansai) and one in the East (Kanto). In the Kanto tradition, the eel is slit down its back and butterflied, then skewered before being grilled for the first time, after which it is steamed in a bouillon and baked with sauce. This results in a tender, flaky eel. The Kansai style, in contrast, begins with opening the belly after which the eel is skewered and grilled over charcoal. Unlike in Kanto, the eel is not steamed. Kansai style eel is crispy and chewy. The boundary between these two cooking traditions is said to be near Okazaki city, Aichi prefecture. Aichi borders to Gifu, where Tajimi is located. While privately owned restaurants in Tajimi follow tradition and cook the eel Kansai style, chain restaurants may have the Kanto variety on their menu.

Eel is a nutritious food rich in protein, Vitamin A, B1, B2, D, E, as well as DHA, EPA, and minerals (iron, lead, calcium and copper) (See Note 1). People on the Japanese islands have enjoyed eel for millennia. Bones from eel were excavated from archaeological finds dating back 5000 years in time. The first mention of eel in literature is in the Manyoshu (万葉集, literally "Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves"), which is the oldest existing collection of Japanese poetry, compiled sometime after AD 759. The oldest known eel recipes date back to AD 1300, and illustrate how radically different the cooking methods were in those days. The present cooking method of slicing the eel open and adding a sauce was introduced in the 18th century.Because of the fat in the eel cooks developed a special type of thick and sweetened soy sauce based four ingredients – soy sauce, mirin, sugar, and sake. You can make it yourself, and people have discovered that unagi sauce is " delicious on many kinds of BBQ dishes, such as grilled meat, grilled fish, grilled tofu, grilled mushrooms, grilled rice ball (Yaki Onigiri) ".

Kabayaki is one popular way of grilling eel (unagi in Japanese) and other seafood. It became popular during the Edo period (1603 - 1868) to eat kabayaki during the summer to gain stamina. There is a promotional poster ( 江戸前大蒲焼番付 or the "Edomae Kabayaki Ranking") from the period that advertises 221 unagiya. However, only paying advertisers are included, and the real number of unagiya in Edo, a city of a million citizens, may have been around 400 according to one estimate.

Unagi no kabayaki is usually served with freshly steamed white rice. When served in a donburi type large bowl filled with steamed white rice and topped with fillets of kabayaki eel it is called unadon. That is by far the most popular unagi dish here in Tajimi. Why? Because it's easy to pick up the food from the round bowl with chopsticks. You can finish the meal quickly, and that suits the spirit of the traditional Tajimi eel restaurant customer.

Tajimi is a tradesmen's town. The city is famous for pottery, and people who traded the wares needed to bring their customers somewhere to dine them. Eager to get down to business as they were they didn't want to spend too much time enjoying the meal. Unadon was the perfect solution - a quick yet tasty meal, not too cheap and not too expensive. For the same reason, another standard way of serving eel, unajū, is far less prevalent in this city. Unajū is served in an exclusive lacquer jubako - a square "bento box" - which is harder to pick up the food from using chopsticks.

Tajimi is a tradesmen's town. The city is famous for pottery, and people who traded the wares needed to bring their customers somewhere to dine them. Eager to get down to business as they were they didn't want to spend too much time enjoying the meal. Unadon was the perfect solution - a quick yet tasty meal, not too cheap and not too expensive. For the same reason, another standard way of serving eel, unajū, is far less prevalent in this city. Unajū is served in an exclusive lacquer jubako - a square "bento box" - which is harder to pick up the food from using chopsticks.

Eel is not indeed a fast food dish. The cooking process takes at least 20 minutes and should start upon an order for the meal to taste its best. People will often judge a restaurant by the time it takes to serve the meal. If served after, say, only five minutes, the dish was cooked beforehand. There was a saying in Edo (Tokyo before 1868) that "He who is a hurry to get served at the unagiya has no style". Unagi is eel in Japanese, and unagiya means "eel restaurant". The edokko - the dwellers of Edo - were famous for their impatience and love for fast food, but, as the saying goes, "be patient at the unagiya and enjoy your pickles and your sake".

EEL AND POTTERY WORKERS

As mentioned in the beginning, there is an increase in customers to Mr Murate's restaurant during the summer season. But he doesn't seem so sure that summer is the best time to eat eel. Indeed, according to a program broadcast by Fuji Television (see note 2), although there is a custom in Japan to have eel on the day of the ox celebrations at midsummer or as a relief from natsubate (summer heat fatigue), others claim it tastes best from late autumn to early winter. Eel need to eat plenty of nutrients during that season to survive without food during winter hibernation (see note 3). There is also research that indicates that eating nutritious food like eel has little effect on natsubate (see note 4).

What about local customers, then? Local people here will tell you that workers at the kilns have always liked to eat eel to stay healthy. Work at the kilns was arduous labour, and there was also the heat from the firings, which must have been especially tough to endure during the summer. Summer temperatures in Tajimi are among the highest in the country.

What about local customers, then? Local people here will tell you that workers at the kilns have always liked to eat eel to stay healthy. Work at the kilns was arduous labour, and there was also the heat from the firings, which must have been especially tough to endure during the summer. Summer temperatures in Tajimi are among the highest in the country.

"Eel has always been a greatly treasured food in this region," Mr Murate explains. "When we kept a stock of eel in cages in the Toki river here. My grandfather had to stand watch, guarding them against thieves. When there were heavy rains and flooding the eel would escape from their cages. At those times people would come to try to steal them from us. These days we exclusively use farmed eel, however. There are no eel fishers here anymore. It's not possible to make a living from eel fishing any longer."

His story reminds me of my wife's grandmother has told me. Her parents were kamayaki - artisans who fired pottery. The heat from the kiln and hard labour took a heavy toll on their bodies, and they needed energy-rich food to stay healthy. In the belief that eel consumption will help, they always kept a stock of eel in cages in a watercourse near their house. A fishmonger would come around regularly and replenish the stock. Perhaps his eel were escapees from the Murate cages on occasion, who knows?

His story reminds me of my wife's grandmother has told me. Her parents were kamayaki - artisans who fired pottery. The heat from the kiln and hard labour took a heavy toll on their bodies, and they needed energy-rich food to stay healthy. In the belief that eel consumption will help, they always kept a stock of eel in cages in a watercourse near their house. A fishmonger would come around regularly and replenish the stock. Perhaps his eel were escapees from the Murate cages on occasion, who knows?

Those days are long gone, and the variety of customers at Uoseki has increased accordingly.

"We still have a lot of business customers, but these days there are also many families frequenting our restaurant, as well as couples. Business customers often visit us after a deal. And there is of course settai, that is business people who bring their customers here to give them a treat and create a good relationship with their customers. Furthermore, we have a lot of customers coming here from Nagoya on a day off. They come in groups of three to five. When it comes to foreigners, many are ladies, travelling alone. I guess they must find out about us somewhere on the Net. Tomorrow a person comes from Taiwan to research their travelling business. We don't have as many Americans or Europeans yet, but they are slowly on the rise too. I think there is less information about us reaching those markets."

"We still have a lot of business customers, but these days there are also many families frequenting our restaurant, as well as couples. Business customers often visit us after a deal. And there is of course settai, that is business people who bring their customers here to give them a treat and create a good relationship with their customers. Furthermore, we have a lot of customers coming here from Nagoya on a day off. They come in groups of three to five. When it comes to foreigners, many are ladies, travelling alone. I guess they must find out about us somewhere on the Net. Tomorrow a person comes from Taiwan to research their travelling business. We don't have as many Americans or Europeans yet, but they are slowly on the rise too. I think there is less information about us reaching those markets."

grilling takes a lifetime to learn

There is an old saying about the mastery of eel cooking," says Mr Murate: "It takes three years before you can do a proper wari, that is to slit and butterfly an eel properly. Next you must master the kushiuchi, or skewering. That takes five years. Skewering one eel is not that hard, but when you do three or four at a time it becomes very difficult to strike a balance. After that comes the grilling over charcoal. Mastering that art is said to take a lifetime. You can grill using electricity or gas and achieve an even result, but with charcoal - which is our preferred method - it is a different story. Even if you start out under good conditions the charcoal gradually turns into ash and everything changes. You have to constantly adjust to this, and that is very difficult. It is a skill that takes a lifetime to acquire. Gas and electricity is OK, but to cook really tasty eel you have to use charcoal - and the best charcoal possible. Otherwise the temperature will not reach an ideal level, or the eel may catch a bad smell from charcoal. When low quality charcoal burns the gas exhaust affects the smell of the eel.

"I like to use knives from Seki, a town neighbouring Tajimi, " Mr Murate says. "The town is famous for its knife making tradition. "By the way," he says, "Seki also has many good eel restaurants. Just like workers at the kilns here in Tajimi had to endure heat and hard labour, and ate eel to gain new strength, smiths in Seki did the same thing. And just like Tajimi, there is no sea to fish in there. There are other cities famous for eel here in Gifu prefecture, such as Gujo. They have similar conditions to here. There is a river there where they fished eel, and no sea."

a healthy dish - in moderate amounts

"So what is the most delicious way to eat eel?" we ask. " Donburi , in my opinion. Donburi presents a great harmony between the eel, the rice and the tare ." I am curious if Mr Murate is a fan of the local cooking style, but he sidesteps the question. "I lived seven years in Tokyo and enjoyed the eel I had there, but it is a completely different dish in my view. I don't think one style is better than the other. They are simply different."

Is it healthy food? "Well, it's undeniable that it is quite a fatty food. If you are on a diet eel is probably not ideal for you. On the other hand, there are lots of vitamins in eel."

It looks like this writer will need to do a bit more exercise before my next trip to a Tajimi unagiya.

Common eel dishes

- うなぎ定食 ・ 鰻定食 unagi teishoku

eel set meal, with grilled eel, rice, pickles, and miso or eel-liver dashi - うな丼 unadon: served in a bowl and therefor easier to eat than the unajū. This made unadon more popular than the unajū in Tajimi.

- うな重 ・ 鰻重 unajū is served in an exclusive urushi (lacquer) jubako - a square "bento box" . Grilled kabayaki eel "piled" over rice

- 上うな重 jō unajū: deluxe unajū

- かばやき ・ 蒲焼 kabayaki: grilled eel on skewers (without rice), seasoned with tare

- ひつまぶし hitsumabushi: dish based on kabayaki style eel sliced in thin stripes on rice in a ohitsu (round, wooden container for rice). Nagoya style unagi.

- 釜めし kamameshi

- "Kettle rice". A traditional Japanese rice dish cooked in a ceramic pot called a kama.

- タレ tare: A sweet, strong soy sauce

- 備長炭 binchō-tan (or binchō-zumi)

- A "white charcoal" made from ubame oak. Odorless and burns at very high temperature, therefor preferred by unagi cooks.

- しらやき ・ 白焼 shirayaki: "white" eel, grilled plain without sauce

- いかだ(焼) ・ 筏(焼) ikada (yaki): "raft-style," with eels lined up and skewered side by side

- う巻 umaki: grilled eel wrapped in egg omelet (see image in this article)

- うざく uzaku: grilled eel and cucumber in a soy-vinegar sauce

- 八幡巻 ・ やわた巻 yawata-maki: Eel rolled raw around burdock strips and grilled with tare.

- きもやき ・ 肝焼 kimoyaki: eel livers grilled BBQ style and served with grated radish

- きもすい ・ 肝吸い kimosui: clear dashi soup made with eel livers

Notes

1) 「日本人とうなぎ」東京新聞サンデー版2012年4月15日 The Japanese and Eel", Tokyo Shinbun, Sunday edition, April 15, 2012

2) 『ホンマでっか!?TV』(フジテレビ系列、2016年8月3日放送分)「間違えだらけの夏の習慣 / 夏バテは自律神経の乱れにより脳が疲れて起こる」Source: "Could it be true!?" (Fuji Television broadcast, August 3, 2016) "Summer traditions that get it all wrong/Natsubate is a brain fatigue caused by a stressed autonomic nervous system")

3) "With the onset of winter eels hibernate to deep mud in backwaters, swampy areas or drains where they lie dormant until spring. Hibernation has been amply confirmed by trapping and observation in the winter months in page 49 rivers and streams and by recovery of the dormant eels during swamp excavations." Source: Victoria, University of Wellington, TUATARA: VOLUME 3, ISSUE 2, AUGUST 1950, "New Zealand Fresh Water Eels".

4) 大阪市立大学大学院特任教授の梶本修身によれば、食肉など栄養価の高いものを食することが当たり前になった現代においてはエネルギーやビタミン等の栄養不足が原因で夏バテになることは考えにくく、夏バテ防止のためにうなぎを食べるという行為は医学的根拠に乏しいとされ、効果があまりないとしている. According to Professor Shushin Kajimoto at Osaka Universtity, it is highly questionable that eating high energy foods and vitamins has a positive effect on natsubate. Little evidence supports the idea that eel consumption helps reduce summer fatigue. Source: "Could it be true!?" (Fuji Television broadcast, August 3, 2016) "Summer traditions that get it all wrong/Natsubate is a brain fatigue caused by a stressed autonomic nervous system")

Images

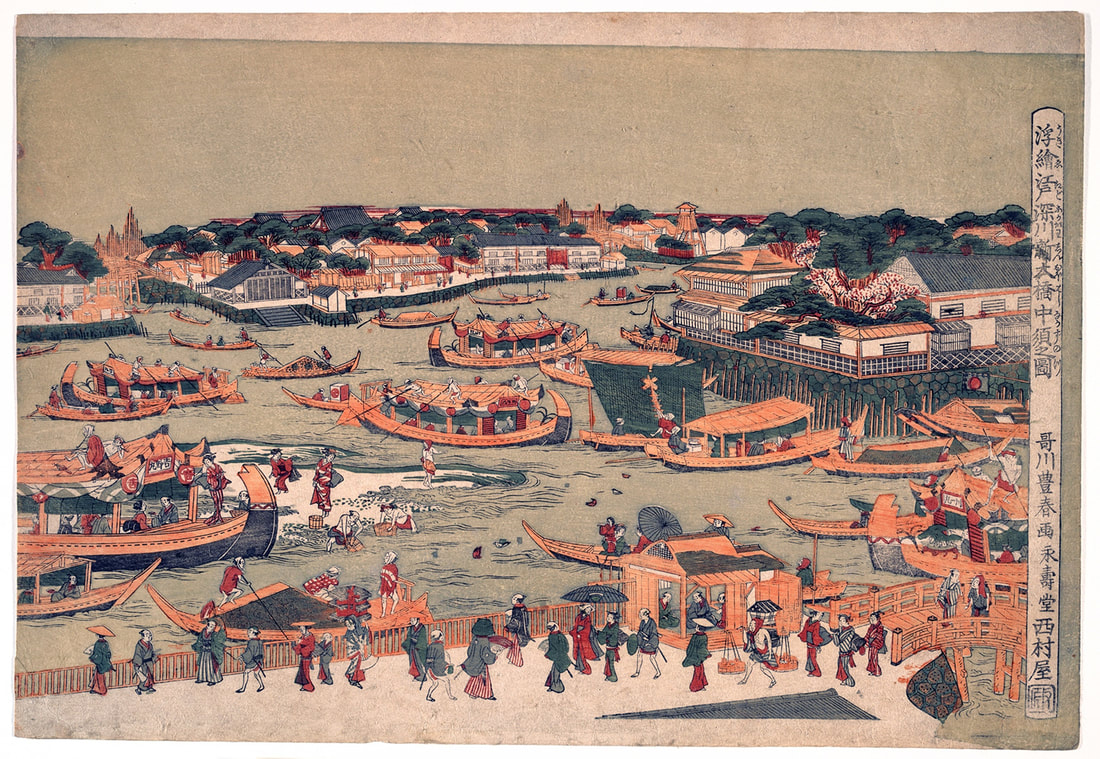

- New Great Bridge at Naka Zu in Edo Utagawa Toyoharu (Japanese, 1735–1814). Public domain. Metropolitan Museum of Art.