"Shino ware (志野焼 Shino-yaki) is Japanese pottery, usually stoneware, originally from Mino Province, in present-day Gifu Prefecture, Japan. It emerged in the 16th century. It is identified by thick white glazes, red scorch marks, and a texture of small holes. Some experts believe it should not treated as distinct from Oribe ware but described as 'white Oribe', with the pottery usually called just Oribe described as 'green Oribe' instead." Source: Wikipedia

the true origin of Shino ware

"The glory days of Mino have influenced eight contemporary potters and these include such legends as Rosanjin Kitaoji (1883-1985), Arakawa Toyozo (1895-1985) and Kato Tokuro (1898-1985)." - Robert Yellin

English language sources often speak of Oribe and Shino as styles originated in Mino, but exactly where in Mino were they invented? According to the English language entry in Wikipedia, "Mino ware (美濃焼 Mino-yaki) refers to Japanese pottery that was produced in Mino Province around the towns of Toki and Minokamo in Gifu Prefecture, central Japan".

If we take a look at the Japanese entry, it says:

"Mino-yaki (Mino Ware), is the general term for pottery produced in Gifu Prefecture, in the cities of Toki, Tajimi, Mizunami, and Kani." Aha! There was no mention of neither Tajimi, nor Mizunami or Kani in the English entry. It continues: "In 1978, on the 22nd of July, Minoyaki was officially recognized by the then International Ministry of Trade and Industry as a traditional Japanese crafts form. Minoyaki is mainly produced in the Tono region of Gifu, which is Japan's largest production base for ceramics and porcelain, commanding approximately half of the total Japanese market."

Tajimi sits smack in the Tono region, and the Tono dialect - a wonderful, colourful tongue - is spoken here. But it wouldn't be quite true to say that Tajimi is the origin of Shino ware. Confusingly, all the four styles of pottery listed as Mino ware - Ki-seto, Setoguro, Shino and Oribe - are also regarded as traditional Seto ware. Seto, a city in neighboring Aichi Prefecture, is a well established brand in Japanese pottery - more famous, perhaps, than Mino.

As we have seen in previous installments of this series, potters fled Seto during the dangerous days of civil war in the middle ages, and settled down in Mino where they continued to produce pottery and develop their craft. It was earlier thought that all of the Seto ware pottery originated in Seto, but this seems to be a misconception. An epoch breaking discovery in the last century set the record straight when it comes to the origin of Shino ware.

Tajimi born Toyozō Arakawa (1894 - 1985), a famous potter in the Shino ware tradition, set out on a search for the origin of the Momoyama style of Shino pottery. He would make a discovery that challenged the widely held opinion at that time that Shino ware originated in the city of Seto.

As a young man, Arakawa worked at the kiln of Rosanjin (1883 - 1959) a noted artist and epicure in Kamakura. Rosanjin had an interest in lost traditions from ancient China and Japan, and based his pottery style and techniques on them. China had a huge influence on Japanese pottery culture, and there were few cases where one could say the origin of a form was Japan. Shino-ware was an exception. It is regarded as the only form of white pottery that can truly be said to have originated in Japan. Perhaps this drew Arakawa's attention. He would spend a life-time recreating and perfecting the feldspar glazing, perfect form, excellent firing, exceptional clay flavor, and brilliant fire colors that were all characteristics of the lost art of Shino-ware.

What was it that set him out on this journey?

The year was 1930. Arakawa and Rozanjin (1883 – 1959), were up late one night, admiring Momoyama era pottery, when they noticed something odd on the inside of the takadai (foot) of a Momoyama era Shino ware tea bowl.

If we take a look at the Japanese entry, it says:

"Mino-yaki (Mino Ware), is the general term for pottery produced in Gifu Prefecture, in the cities of Toki, Tajimi, Mizunami, and Kani." Aha! There was no mention of neither Tajimi, nor Mizunami or Kani in the English entry. It continues: "In 1978, on the 22nd of July, Minoyaki was officially recognized by the then International Ministry of Trade and Industry as a traditional Japanese crafts form. Minoyaki is mainly produced in the Tono region of Gifu, which is Japan's largest production base for ceramics and porcelain, commanding approximately half of the total Japanese market."

Tajimi sits smack in the Tono region, and the Tono dialect - a wonderful, colourful tongue - is spoken here. But it wouldn't be quite true to say that Tajimi is the origin of Shino ware. Confusingly, all the four styles of pottery listed as Mino ware - Ki-seto, Setoguro, Shino and Oribe - are also regarded as traditional Seto ware. Seto, a city in neighboring Aichi Prefecture, is a well established brand in Japanese pottery - more famous, perhaps, than Mino.

As we have seen in previous installments of this series, potters fled Seto during the dangerous days of civil war in the middle ages, and settled down in Mino where they continued to produce pottery and develop their craft. It was earlier thought that all of the Seto ware pottery originated in Seto, but this seems to be a misconception. An epoch breaking discovery in the last century set the record straight when it comes to the origin of Shino ware.

Tajimi born Toyozō Arakawa (1894 - 1985), a famous potter in the Shino ware tradition, set out on a search for the origin of the Momoyama style of Shino pottery. He would make a discovery that challenged the widely held opinion at that time that Shino ware originated in the city of Seto.

As a young man, Arakawa worked at the kiln of Rosanjin (1883 - 1959) a noted artist and epicure in Kamakura. Rosanjin had an interest in lost traditions from ancient China and Japan, and based his pottery style and techniques on them. China had a huge influence on Japanese pottery culture, and there were few cases where one could say the origin of a form was Japan. Shino-ware was an exception. It is regarded as the only form of white pottery that can truly be said to have originated in Japan. Perhaps this drew Arakawa's attention. He would spend a life-time recreating and perfecting the feldspar glazing, perfect form, excellent firing, exceptional clay flavor, and brilliant fire colors that were all characteristics of the lost art of Shino-ware.

What was it that set him out on this journey?

The year was 1930. Arakawa and Rozanjin (1883 – 1959), were up late one night, admiring Momoyama era pottery, when they noticed something odd on the inside of the takadai (foot) of a Momoyama era Shino ware tea bowl.

"They say these things have been produced in Seto since ancient times," said Arakawa, "but I have a feeling this came from somewhere else. Look, there is red clay in the inside of the takadai."

Rozanjin had his doubts, and fell asleep in a while. The though kept nagging in Arakawa's mind however, and he remembered that this particular clay could be found at the old Ohiya kiln in Tajimi. His search there didn't result in anything significant, however.

After a tip that clues might be found at the old ruin of the Momoyama era Ogaya kiln in Kukuri, Kani city, Arakawa and his friend Rosanjin went up in the mountains to investigate. There, rooting around in the old rubble in the woods, they found a shard of pottery that had a bamboo shoot design painted on it. It was a typical Shino ware design. According to his diary, walking home, Arakawa and Rosanjin stopped many times to admire the old shard in the moonlight. This was the first time ever a Momoyama era production facility for Shino ware had been discovered. The following diggings proved that Shino and Oribe glazed work of the Momoyama and early Edo period in Japan had been manufactured in Mino rather than in the Seto area.

Arakawa went on to produce Shino ware at a kiln which he designed in the Momoyama tradition and built near the place of the discovery. He was awarded the title "Living National Treasure" in 1955 for his work concerning Shino and Setoguro pottery and the preservation of production techniques of important intangible cultural assets.

It is important to note how vital the quality of the clay is for the final product. I came to realise this some time ago when I visited an exhibition by a local artist. There was a construction project going on on the neighboring property. A huge hole was being dug in the ground by workmen - it must have been at least ten meters deep and looked like a mining project. Apparently the reason for this undertaking was construction regulations. The property sat on the edge of a steep hill. A private house was going to be built here. To insure it wouldn't become unstable at an earthquake the foundation had to be this deep. Anyhow, the potter told me that a rare and valuable clay - one used for Shino ware - had been discovered deep down in the whole. "This is huge", she said. "That clay is worth its weight in gold." She explained that when these discoveries are made by a construction company, some famous potter will be contacted and will enter a secret agreement for excavation of the clay. "The ground will quickly be covered to hide the treasure from suspicious eyes", she said, "and the potter will come digging when nobody is looking." Considering that a top potter can sell a Mino ware tea cup for a sum equivalent to the price of an expensive car, this is quite understandable.

It is this clay that has served as the foundation for the pottery culture here in Tajimi and the other cities in Mino. It was the clay that made the potters from Seto settle down here. When there is a heavy rainfall, the water in creek behind our house will turn into a whitish grey colour because of the clay that is being washed down from the mountains.

Rozanjin had his doubts, and fell asleep in a while. The though kept nagging in Arakawa's mind however, and he remembered that this particular clay could be found at the old Ohiya kiln in Tajimi. His search there didn't result in anything significant, however.

After a tip that clues might be found at the old ruin of the Momoyama era Ogaya kiln in Kukuri, Kani city, Arakawa and his friend Rosanjin went up in the mountains to investigate. There, rooting around in the old rubble in the woods, they found a shard of pottery that had a bamboo shoot design painted on it. It was a typical Shino ware design. According to his diary, walking home, Arakawa and Rosanjin stopped many times to admire the old shard in the moonlight. This was the first time ever a Momoyama era production facility for Shino ware had been discovered. The following diggings proved that Shino and Oribe glazed work of the Momoyama and early Edo period in Japan had been manufactured in Mino rather than in the Seto area.

Arakawa went on to produce Shino ware at a kiln which he designed in the Momoyama tradition and built near the place of the discovery. He was awarded the title "Living National Treasure" in 1955 for his work concerning Shino and Setoguro pottery and the preservation of production techniques of important intangible cultural assets.

It is important to note how vital the quality of the clay is for the final product. I came to realise this some time ago when I visited an exhibition by a local artist. There was a construction project going on on the neighboring property. A huge hole was being dug in the ground by workmen - it must have been at least ten meters deep and looked like a mining project. Apparently the reason for this undertaking was construction regulations. The property sat on the edge of a steep hill. A private house was going to be built here. To insure it wouldn't become unstable at an earthquake the foundation had to be this deep. Anyhow, the potter told me that a rare and valuable clay - one used for Shino ware - had been discovered deep down in the whole. "This is huge", she said. "That clay is worth its weight in gold." She explained that when these discoveries are made by a construction company, some famous potter will be contacted and will enter a secret agreement for excavation of the clay. "The ground will quickly be covered to hide the treasure from suspicious eyes", she said, "and the potter will come digging when nobody is looking." Considering that a top potter can sell a Mino ware tea cup for a sum equivalent to the price of an expensive car, this is quite understandable.

It is this clay that has served as the foundation for the pottery culture here in Tajimi and the other cities in Mino. It was the clay that made the potters from Seto settle down here. When there is a heavy rainfall, the water in creek behind our house will turn into a whitish grey colour because of the clay that is being washed down from the mountains.

how tajimi came to be a pottery trading centre

As we have seen in previous installments, the Daimyo feudal lords highly admired such tea vessels, bowls, pots and utensils with unique styles of oribe in their day. To people like Furuta Oribe it was an obsession, even. More emphasis has been put on daily necessities since the early Edo period (1603–1867). There was a large and growing market that needed to be served. The Edo era was a long period of peace and prosperity in Japan. Well, prosperity is a relative term, but many traders in Edo (today known as Tokyo) and elsewhere made very good money, and there was plenty of work for laborers and craftsmen in the city. The construction of the massive Edo castle for the ruling Tokugawa shogunate was a huge undertaking and large numbers of able workers moved into the city.

During the Edo era, Tajimi belonged to a feudal domain of Owari (尾張藩 Owari han). Located in what is now the western part of Aichi Prefecture, it encompassed parts of Owari, Mino, and Shinano provinces. Its headquarters were at Nagoya Castle. At its peak, it was rated at 619,500 koku, and was the largest holding of the Tokugawa clan apart from the shogunal lands.

By order from the Owari han, the five towns in the Mino region must sell all their goods via the domain's whole sellers. Any trader that was caught selling his wares elsewhere had his goods confiscated. However, towards the end of the feudal era, foreigners started to enter the country again after the long period of isolation, and the Japanese became aware of the contradiction in these kinds of trade restrictions. Wasn't there a better way to do business?

By the middle of the period, production moved away from exclusive tea utensils to iron or large scale production of ash glazed goods for every day use, such as bowls, plates, sake bottles and other tableware. Ofukeyu and hakuyu (white glaze) ceramics, similar to Chinese celadon porcelain, were manufactured in large numbers and distributed across the nation. In general only one type of clay was used, but towards the end of the period feldspar and silica was mixed into the clay, and the production of china became widespread.

Many traditional kilns in Mino went out of business during the Edo era. Production continued in Seto however, and this is how the region came to overshadow Mino in the public mind as the cultural home of Mino/Seto ware.

During the Edo era, Tajimi belonged to a feudal domain of Owari (尾張藩 Owari han). Located in what is now the western part of Aichi Prefecture, it encompassed parts of Owari, Mino, and Shinano provinces. Its headquarters were at Nagoya Castle. At its peak, it was rated at 619,500 koku, and was the largest holding of the Tokugawa clan apart from the shogunal lands.

By order from the Owari han, the five towns in the Mino region must sell all their goods via the domain's whole sellers. Any trader that was caught selling his wares elsewhere had his goods confiscated. However, towards the end of the feudal era, foreigners started to enter the country again after the long period of isolation, and the Japanese became aware of the contradiction in these kinds of trade restrictions. Wasn't there a better way to do business?

By the middle of the period, production moved away from exclusive tea utensils to iron or large scale production of ash glazed goods for every day use, such as bowls, plates, sake bottles and other tableware. Ofukeyu and hakuyu (white glaze) ceramics, similar to Chinese celadon porcelain, were manufactured in large numbers and distributed across the nation. In general only one type of clay was used, but towards the end of the period feldspar and silica was mixed into the clay, and the production of china became widespread.

Many traditional kilns in Mino went out of business during the Edo era. Production continued in Seto however, and this is how the region came to overshadow Mino in the public mind as the cultural home of Mino/Seto ware.

By Tamamura Kozaburo (OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The feudal regime in Japan finally collapsed in 1868 with the Meiji Restauration, whereby Emperor Meiji moved from Kyoto to Edo, which was renamed Tokyo. A period of fast modernization began in the country, which is unparalleled in the world.

With the introduction of mass production introduced in the Meiji era (1868–1912), Mino ware became widely available, but there was no effort to sell the brand. Rather, the business minded traders in Tajimi saw a chance to sell affordable, high quality ceramics rather than exclusive hand crafted items in the Mino tradition, and they would do so with great success. The build-up over the last century has resulted in a production centre in the Mino area that today commands half of the total market in Japan. Many people I have spoken to here in Tajimi complains that there have never been a concerted effort to establish Mino ware as a brand. Others claim that Mino ware really encompasses much more than the four traditional classic Momoyama era glazes, which makes it harder to market.

With the introduction of mass production introduced in the Meiji era (1868–1912), Mino ware became widely available, but there was no effort to sell the brand. Rather, the business minded traders in Tajimi saw a chance to sell affordable, high quality ceramics rather than exclusive hand crafted items in the Mino tradition, and they would do so with great success. The build-up over the last century has resulted in a production centre in the Mino area that today commands half of the total market in Japan. Many people I have spoken to here in Tajimi complains that there have never been a concerted effort to establish Mino ware as a brand. Others claim that Mino ware really encompasses much more than the four traditional classic Momoyama era glazes, which makes it harder to market.

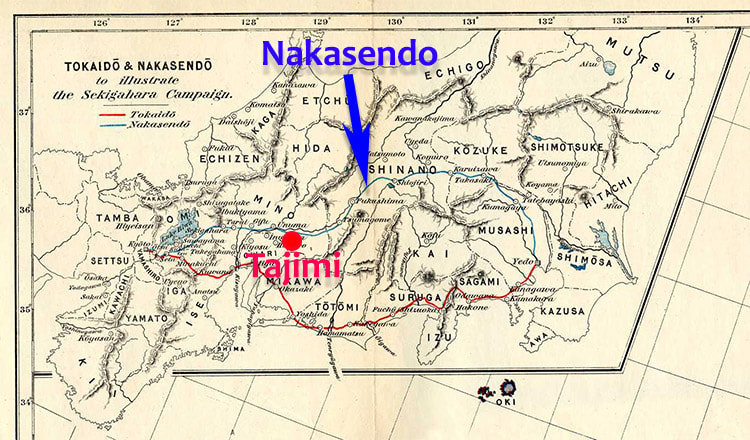

One factor that played into the growing importance of Tajimi was the new Chuo Train line, that opened new distribution opportunities for manufacturers located in the city. Previously, the Nakasendo road had been the main route connecting Kyoto and Edo (today Tokyo) through the inland, while the Tokaido on the Pacific coast connected the urban centres on the coast to the two cities.

Porcelain manufacturer Enji Nishiura (1846 - 1895) and ceramics industrialist Sukesaburo Kato (1857 - 1908) were among the first to open new trade routes. Nishiura won international fame by exhibiting at the World Expo in Paris 1889 World Fair, where the Eiffel Tower, completed the same year, and served as the entrance arch. Nishiura's work, which originally focused on Western-style table wares with Japanese designs in underglaze-blue was greatly appreciated by the Western public, and he later entered the US market with great success. His son started a large scale operation (120 employees) in Nagoya, to mass-produce underglaze-decorated porcelain, again with Japanese motifs in Western taste, using innovative techniques.

Porcelain manufacturer Enji Nishiura (1846 - 1895) and ceramics industrialist Sukesaburo Kato (1857 - 1908) were among the first to open new trade routes. Nishiura won international fame by exhibiting at the World Expo in Paris 1889 World Fair, where the Eiffel Tower, completed the same year, and served as the entrance arch. Nishiura's work, which originally focused on Western-style table wares with Japanese designs in underglaze-blue was greatly appreciated by the Western public, and he later entered the US market with great success. His son started a large scale operation (120 employees) in Nagoya, to mass-produce underglaze-decorated porcelain, again with Japanese motifs in Western taste, using innovative techniques.

Kato, nick named "the Pottery Shogun" because of his aggressive business strategy, established himself in China, India, the US, and South Africa, and published the first ceramics trade newspaper in Japan in 1894.

Tajimi began to bloom as a pottery trades town, and while there have been ups and downs, it is still today a city at the heart of the ceramics industry in the Mino region. Not the least, Tajimi is a ceramics Mecca of sorts in Japan, since virtually all kinds of ceramics are produced and sold here, and the city has a solid infrastructure also when it comes to education in the ceramics field.

In the next installment we will need some of the modern potters in Tajimi and take a look what the ceramics industry here looks like today.

Tajimi began to bloom as a pottery trades town, and while there have been ups and downs, it is still today a city at the heart of the ceramics industry in the Mino region. Not the least, Tajimi is a ceramics Mecca of sorts in Japan, since virtually all kinds of ceramics are produced and sold here, and the city has a solid infrastructure also when it comes to education in the ceramics field.

In the next installment we will need some of the modern potters in Tajimi and take a look what the ceramics industry here looks like today.