THE POTTER's Perspective

By Hans Karlsson

If you missed the first installment

In the initial segment of this piece, I shared insights about the enchanting tea ceremony, a time-honored cultural treasure of Japan. In that previous installment, we delved into the ways one can personally experience this tradition during a visit to our beloved Gifu Prefecture. Now, we embark on a fresh exploration, shifting our gaze to the ceremony's essence through the eyes of two gifted potters. This time, our focal point is the narrative, as we unravel the compelling story concealed within the heart of the ceremony—the teabowl. It is the very core of this ritual, and within its form lies a tale waiting to be unveiled.

VR-FRIENDLY ARTICLE

Ikuhiko Shibata: "When I think of the Tea ceremony the word 'poison' keeps popping up in my mind"

Use your mouse to move the image

This video is viewable in 3D. Use a VR headset such as the Meta Quest 3 and access the video by searching for "Ikuhiko Shibata" and selecting the 180 VR tag in the YouTube VR application.

Shibata explains here how he turned the wheel "an extra rotation" to get this nice result.

Shibata explains here how he turned the wheel "an extra rotation" to get this nice result.

As a devoted practitioner of the tea ceremony, Potter Ikuhiko Shibata finds profound significance in tracing its origins. For him, this exploration serves as a wellspring of inspiration, infusing his artistic creations with a profound depth of meaning and an unparalleled authenticity. I was privileged to receive an invitation to share a moment with Shibata in his unassuming tearoom, nestled in the corner of his studio. There, he had thoughtfully curated an array of tea utensils, each a product of his own craftsmanship and devotion.

“I am still a beginner student of the tea ceremony. There are so many things in Sado (the tea ceremony) to memorise. It’s overwhelming, but I have many impressions and feelings about this culture. I believe that o-cha (the tea ceremony) provided the samurai with an environment for conversation back in the times when our country was engulfed in a civil war. I imagine they met in some small tea room with allies as well as enemies to negotiate. It’s an awkward situation, and so the various tools of the ocha-kai (tea party) came in handy.

"Imagine, for example, a host, a feudal lord, showing a chawan to his guest:" 'This teabowl, it’s marvellous! It’s made by a great master; let me tell you about him’, and the host tells the story of that tea bowl." "Or,” master Shibata continues, “the lord might say, ‘take this chashaku spoon; it’s made by this famous artisan. He's such a gifted man.’ "Or, maybe it was the mizusashi (cold water container) or a kakejiku hanging scroll adorned with calligraphy by some famous monk.”

“In spite of the tiny world of the tearoom they were sitting in,” he continues, “there were a number of ice-breaking topics to bring up to lighten up the mood in a high-stakes meeting in the midst of war. This was a way to create a friendly atmosphere in a dangerous time. The tearoom is a place of peace; the entrance to the room is tiny, so you can’t rush in with swords drawn. Weapons of war are to be left outside.”

“Another thing is the tea ceremony itself. As you know, when the guests receive their bowl of maccha tea, they are supposed to turn it before drinking. Let’s say the host is planning to poison the guest. He may apply some poison to the edge of the bowl and tell the guest to drink from it. By allowing the guest to turn the bowl, it gives him the freedom to choose from where to drink, at least symbolically; in most forms of the ceremony, one turns the bowl 45 degrees.”

“By the same token, the host must return half of the water he scoops from the kama (iron kettle) with the hishaku (bamboo water ladle) to transfer water to the bowl. He only empties half of the water from the hishaku into the bowl and returns the rest. This is another assurance that he will not poison the guest, as the host will drink the same water. The same goes for cleaning the chashaku bamboo tea scoop, which I feel is also connected to safety by demonstrating that there is nothing harmful or pointy on the scoop." Shibata-sensei is probably thinking about something steeped in poison again. "I heard this from my teacher," he adds, "an omotesenke master here in Gifu Prefecture."

“Well, these are all my theories, but as I study Sado (the tea ceremony)—the word poison keeps popping up in my mind. It makes me think of many things about how the ceremony was performed in the troubling days of the long civil war in Japan.”

“Well, these are all my theories, but as I study Sado (the tea ceremony)—the word poison keeps popping up in my mind. It makes me think of many things about how the ceremony was performed in the troubling days of the long civil war in Japan.”

Shibata is making traditional tea utensils, but he also wants to try new things. “Take, for example, this golden chawan and this more plain-looking one,” he says. “Both were thrown on the same wheel and are made according to the same principles. I spin the wheel in a single state of mind.”

“Both bowls were thrown on the same wheel and are made according to the same principles. I spin the wheel in a single state of mind.”

“Time is an important element in this craft,” the potter says. “I was told once (and now he switches to the crude local dialect in Tajimi) ‘never spin the wheel too fast’. "At another time, I was told: ‘this bowl would have needed one more rotation.’ You may wonder what that means. I think the meaning is that with that one rotation, in that short instant, the bowl changes shape into something beautiful. That makes you feel a sense of flow in time. I think that feeling is part of the Minoware potter’s tradition.” All this is part of the story of pottery.

Another part of the Mino tradition, he explains, is rough clay. “What we call good clay does not mean good quality clay. In our neighbouring city, Seto, the clay is really high quality. You can make many good bowls in a day with that clay. It all goes very smoothly, but the clay here is rough, and however hard you try, the bowl will come out uneven and warped.

That connects to the underlying theme of the tea ceremony—the wabi-sabi—telling us that imperfection is beauty. “I go regularly to the US to teach pottery, and every time they ask about this mysterious wabi-sabi. I never seem to be able to explain. It’s hard to understand, even for the Japanese. This is quite different from China, where people love the beauty of symmetry. Perhaps it’s only us Japanese who like strangely bent, warped asymmetrical things.”

That connects to the underlying theme of the tea ceremony—the wabi-sabi—telling us that imperfection is beauty. “I go regularly to the US to teach pottery, and every time they ask about this mysterious wabi-sabi. I never seem to be able to explain. It’s hard to understand, even for the Japanese. This is quite different from China, where people love the beauty of symmetry. Perhaps it’s only us Japanese who like strangely bent, warped asymmetrical things.”

By Chris Spackman - the en:pictures section of OpenHistory http://www.openhistory.org/pics/castle_and_kenrokuen/html/2002-04-03_07-31-19.html, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=54693

I ask Shibata if he thinks about how to make these warped bowls so they fit well in the hand and work well in the tea ceremony. “No, not really, but a lot of the time they just come out as if they were made for Sado. They have just the right, warped shape. If you think about it, a human hand works better with bent things. The hand is flexible enough to find a comfortable grip.”

Shibata gets up to get a gift from a person he met coincidentally. The man passed away from cancer. His hobby was making chashaku. The potter slides the slender spoon out of its case and shows it. It’s a thing of beauty. It has a name written on it: Kokoro wa mizu no gotoshi (心如水)—'The mind is like water’ (See Notes below). "This is made from bamboo,” Shibata explains. “You have to find one that bends exactly the way you need to make a spoon with this shape. This is a precious item to me. The man gave it to me as a present shortly before he passed away. It’s a fine example of how everything in the tearoom has a story, and the room is a space to tell those stories."

Indeed, there is much depth in just those three characters written on the chashaku case. The man who wrote them is now gone. What made him choose this expression? Was he thinking about the end that was approaching? Did he wish to be like the water—calm, clear, and adaptable—to meet his final days?

Shibata-sensei slides the slender, beautiful spoon back into the case. “I think stories are the essence of the tea ceremony," he says. “To create such a room full of stories is at the heart of the tea ceremony, in my view.”

And that brings us to the Mino ware chawan that has the most exciting story to tell of all - the Shiro tenmoku.

Shibata-sensei slides the slender, beautiful spoon back into the case. “I think stories are the essence of the tea ceremony," he says. “To create such a room full of stories is at the heart of the tea ceremony, in my view.”

And that brings us to the Mino ware chawan that has the most exciting story to tell of all - the Shiro tenmoku.

The story of the Shirotenmoku

Tajimi is a small city in Japan with a population of 100,000. It is home to the Eihoji temple, which is known for its grandeur and beauty. The temple may be linked to the story of the Shiro tenmoku chawan, as I have written about in a previous article. Sokei Aoyama, a potter and experimental archaeologist who has dedicated years to reengineering the production method of these valuable teabowls, shared his theory with me.

“Buddhist temples in Japan possessed many tea utensils since there was a connection between the tea ceremony and Zen. I believe the tradition arrived at Onada by way of monks travelling between temples. As you know, we have a large and very important Zen temple in Tajimi, the Eihoji. Temples are part of a nationwide network. Eihoji is connected to the Rinsenji in Kyoto, so those Kyoto monks may have brought the tea ceremony and sophisticated tea utensils here. Somewhere in the process of producing a replica Chinese tenmoku, a native form was born. I believe the Shiro tenmoku must have come into existence this way, and that it happened in Onada.”

It seems like traces of an exciting tradition in Japanese pottery have been unearthed at the old kilns of Onada, where fragments of the Shiro tenmoku have been found. Their history goes back many centuries.

To quote a previous article I wrote about these unique bowls:

“[The] white tea bowls have been the subject of debate and fascination throughout the discourse on Japanese pottery in the modern age. [Three] once belonged to the great tea master Takeno Jōō (1502–1555). Jōō lived during the Sengoku (warring states) period of the 16th century in Japan, a time of war and unrest. (Shiro tenmoku: The First Reproduction in 500 years - Part 1)

Two of Jōō's bowls would pass through the hands of some of the giants in Japan’s cultural and political history. Among them were Sen no Rikyū, a master among tea masters. The bowls were passed from generation to generation in some of Japan’s most powerful samurai clans. But this is also a story that took on a new life in our time through the work of Aoyama-sensei, and his efforts to bring back the long-forgotten technique to produce these beautiful bowls. After many years of trying, he realised that this would also require recreating a kiln from the heyday of the Shiro tenmoku.

The choshingama kiln

“I started to recreate an early form of wood-firing kiln up in the mountains at Kokeizan here in Tajimi. I wanted to build an ōgama (literally “big kiln), 7,5 metres long and about 1 metre high—a tunnel in the slope of the hill. I wanted to design it in the image of a kiln from around 1500, a time when they used ash glaze. My goal was to fire Shiro tenmoku the same way the remaining bowls we have must have been fired. However, in the first firing, the pieces came out in the wrong style and colour.

In this video, we visit the Choshingama kiln that is being prepared for firing. We photographed it using a drone and captured a 3D model, which can be viewed here below. The video has graciously been provided by Mimir LLC.

The model has graciously been provided by Mimir LLC.

Aoyama-sensei has spent several decades trying to reengineer the production method of the precious bowls, which was forgotten for five hundred years. His efforts have been recognised by Tajimi City and the Tokugawa Art Museum in Nagoya, but he is still not completely satisfied with his achievements. One of the master's reproductions is now kept by the Tokugawa Art Museum, which also keeps a couple of the few remaining original Shiro tenmoku. These are the ones first owned by Takeno Jōō.

“Takeno’s bowls were most certainly made here in Onada,’ says Aoyama-sensei, “and I have spent my life trying to figure out why this was the place of origin and what materials were used.”

“I set out to fix the kiln to change how the flame and gases would travel inside, thinking about the effects of reduction firing (kangen) and oxidation firing (sanka). By the third firing, I was able to achieve a pretty good reduction firing and came closer to what I wanted. But even so, the bowls looked totally different from those that had been in use for decades, and certainly the remaining originals from five hundred years ago.”

Use your mouse to move the image

This video is viewable in 3D. Use a VR headset such as the Meta Quest 3 and access the video by searching for "Sokei Aoyama" and selecting the 180 VR tag in the YouTube VR application.

Master Aoyama shows the difference between a used Shiro tenmoku and a new one. The video has English voice over.

I had stayed true to the original production method, so what was the problem? The answer is that you have to use the bowls over a long period of time before they start to look like the original Shiro tenmoku.” Tea residue creeps into the fine cracks in the glaze and turns them into a beautiful pattern. And the bottom part of the bowl, which is not covered with glaze, turns brown as tea seeps into the clay material.

“The shirotenmoku must have been fired here,” the master explains, “because only here can you find clay that contains the right materials for making these bowls, and fragments of such bowls have indeed been found here. If you use reduction firing, you will get bluish results, and with oxidation, you will get yellowish results. The clay also influences the colour. The less iron in the clay, the whiter the result. That is the kind of clay that was used for Shiro tenmoku."

The Shiro tenmoku are ideally suited for the tea ceremony, as I noted in an earlier article on this site:

“The bowls embody the heart and spirit of rustic simplicity in tea that Japan has become famous for - the wabicha (wabi tea ceremony). Wabi-sabi has to do with the acceptance of transience and imperfection. Everything in this world wears down and changes; it rusts and becomes dirty and imperfect. To see a special kind of beauty in this change is Sabi. To accept the rust and dirt and to enjoy it is Wabi.”

Taking a close look, you will see that the shapes of the Shiro Tenmoku are indeed not perfect but crooked. This contrasts with Chinese tradition, once viewed as the aesthetic ideal by the tea-drinking upper class in Japan.

While Aoyama-sensei is not actively studying Sado, he is happy to serve maccha in his tea bowls. He jokes that any tea master would scold him for his preparation method. Still, it is a special feeling to drink from these very rare and valuable bowls.

While Aoyama-sensei is not actively studying Sado, he is happy to serve maccha in his tea bowls. He jokes that any tea master would scold him for his preparation method. Still, it is a special feeling to drink from these very rare and valuable bowls.

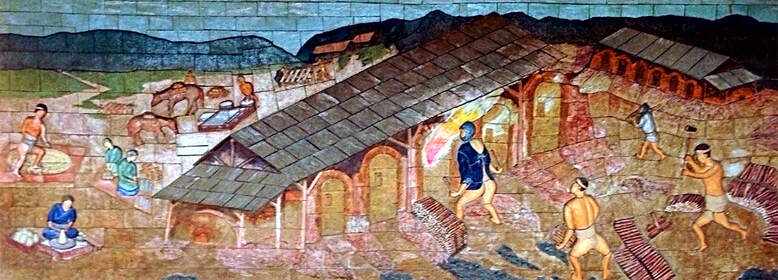

There are remains of three old kilns here in Onada village, where fragments of Shiro tenmoku have been discovered. The kilns were in use between the second half of the 1400s and the middle of the 1500s. “The Shiro tenmoku were regarded as perhaps the most brilliant and spectacular of all tea bowls in Japan and were loved by famous people, such as the mediaeval feudal lord Oda Nobunaga, his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi, as well as his son Hidetsugu, both of whom were Kampaku (regents). Records show one of the remaining originals was later in possession by the daimyo house of Owari Tokugawa, and the other by the daimyo house of Kaga Maeda.

You can tell that Aoyama-sensei is full of passion when he speaks about these precious white tea bowls that originate in his village. “These powerful houses treasured the Shiro tenmoku produced here in Onada, and the precious pieces have passed from owner to owner since the days of the warring states to the Meiji era,” he explains.

the untold story of the original creators

Historical records, quite often, tend to direct their spotlight towards the affluent and influential, overlooking the valiant efforts of the nameless craftsmen who dedicated themselves to producing these astonishing creations exclusively for the privileged few. However, by venturing to the Choshingama kiln during its firing, you shall gain a profound appreciation for the immense physical toil and extensive hours these artisans endured. Through this experience, you will gain insight into the arduous working conditions that the ancient potters faced, braving the piercing chill of winter and the sweltering heat of summer. Each firing only yields a paltry few commendable pieces, if any at all, from a staggering assemblage numbering in the hundreds, having undergone days of meticulous firing. The surplus, unfortunately, succumbs to a fate of naught, underscoring the economic adversity confronting these artisans in times gone by. (For further information on the climbing kilns, refer to this article.)

notes

The Japanese idiom 心如水 (Kokoro wa mizu no gotoshi) means "the mind is like water". It is derived from the eighth chapter of the Tao Te Ching, an ancient Chinese text, which describes the highest form of goodness as being like water. The idiom is often used to describe a state of mind that is calm, clear, and adaptable, like the qualities of water. Source: Conversation with Bing, 1/13/2024

(1) 上善水の如し(じょうぜんみずのごとし)とは? 意味・読み方 .... .

(2) 4月のことば 「心如水(しんはみずのごとし)」 - 齢仙寺雑記帳..

(3) 「心如水」心(しん)は水の如し – 書道家 加地玲泉 書道 .... .

(1) 上善水の如し(じょうぜんみずのごとし)とは? 意味・読み方 .... .

(2) 4月のことば 「心如水(しんはみずのごとし)」 - 齢仙寺雑記帳..

(3) 「心如水」心(しん)は水の如し – 書道家 加地玲泉 書道 .... .