Throughout the history of Japan -in times of disruption and war, as well in times of peace- people have been struggling for power and riches, or purely just to survive. I suppose this is no different from other cultures. Still, the particulars differ from land to land and are always fascinating to study. Mostly the people who appear in the records are men of property or power or both. Here and there we find an empress, or perhaps a mistress of a powerful man. But while they are now lost like shadows to the land of oblivion, there were certainly many commoners who changed the course of history. In our region (traditionally called Mino), a man named Tōso is one such figure. Indeed, his shadow is still apparent in the many festivals and celebrations held in his memory around the city of Tajimi.

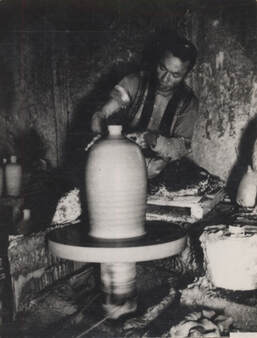

Tajimi lies in the region that was traditionally called Mino, famous for its excellent clay and the ceramics - Mino ware - that have been produced from it across the centuries. Shinto is the native religion of Japan, and the country is also a bastion of Buddhism. But perhaps to many people in Tajimi, Tōsofeels closer to heart. This legendary potter in some ways reminds me of the spirits, or kami, of Shinto, who are believed to once have been real people. I cannot think of any nameless spirit, however, that has played such an important role in securing the livelihood of generations of potters and kiln workers across the centuries. The reason is, of course, that unlike the kami he has a name. In this article, I shall try to paint the story of the significance of this fact.

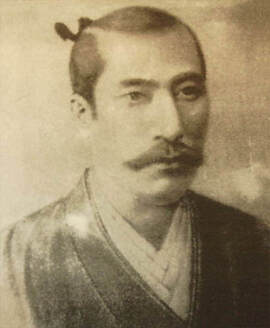

There are monuments scattered around the region in honour of this man -or, rather, men, for it turns out that Tōso is a universal name for the first potter to build a kiln in a place. But perhaps the most famous of such pioneers is master Kato Kagemitsu (1513 - 1585). Who, after escaping from the civil war raging in the neighbouring Seto region, settled down in the Mino region sometime in 1574. Kato became the personal protégé of Oda Nobunaga (1534 – 1582), the most powerful warlord in Japan at the time.

Several hundred years later, in 1902, a monument commemorating Kagemitsu was erected in Hirano village in Tajimi, making him the Mino Tōso of Tajimi. But as we shall see, this wasn’t only to honour the memory of a pioneer. Tōso has played an important part for other reasons throughout the history of the ceramic industry in Mino.

There are monuments scattered around the region in honour of this man -or, rather, men, for it turns out that Tōso is a universal name for the first potter to build a kiln in a place. But perhaps the most famous of such pioneers is master Kato Kagemitsu (1513 - 1585). Who, after escaping from the civil war raging in the neighbouring Seto region, settled down in the Mino region sometime in 1574. Kato became the personal protégé of Oda Nobunaga (1534 – 1582), the most powerful warlord in Japan at the time.

Several hundred years later, in 1902, a monument commemorating Kagemitsu was erected in Hirano village in Tajimi, making him the Mino Tōso of Tajimi. But as we shall see, this wasn’t only to honour the memory of a pioneer. Tōso has played an important part for other reasons throughout the history of the ceramic industry in Mino.

in nobunaga's day

Back in the days of Nobunaga Japan was engulfed in a civil war. The samurai warlord set out on an ambitious project for economic and cultural development. They were to be the building blocks of a unified Japan under his rule. Nobunaga waged a savage war against his opponents to realize his plans.

Paradoxically enough, Kagemitsu, a lowly artisan, was to become a pawn in this chess-like game for power. How could this be? Nobunaga was well aware of the importance of ceramics. Tea utensils were the prime status symbol in the tea room, which was an important communication space for the ruler. An expensive, beautiful tea bowl was a sign of power and wealth, and therefore useful both symbolically and as a gift to influence people one way or the other.

Paradoxically enough, Kagemitsu, a lowly artisan, was to become a pawn in this chess-like game for power. How could this be? Nobunaga was well aware of the importance of ceramics. Tea utensils were the prime status symbol in the tea room, which was an important communication space for the ruler. An expensive, beautiful tea bowl was a sign of power and wealth, and therefore useful both symbolically and as a gift to influence people one way or the other.

While Nobunaga was a brutal suppressor of opponents, he also saw the value in culture as a building block for the unification of the country. He was a keen student of the tea ceremony, and very much admired Chinese tea bowls - works that were considered superior to anything else.

“It is believed that in order to foster kilns in Mino capable of producing bowls surpassing even [what the Chinese could make], Nobunaga took decisive action,” writes Katsuya Nishimura at the Oribe Art Museum. “His goal was to cultivate the ceramics industry in the region. To that end, he put in place a protectionist legislation. I believe Nobunaga was the inventor of the idea of governmental ceramics furnaces”. This was a national policy put in place by the most powerful in Japan at the time, Oda Nobunaga and [his successor] Toyotomi Hideyoshi, by which kilns were firmly put under control by local lords or administration (1).

Why was this important? First, the exquisite tea bowls and utensils that were so sought after by the samurai elite had a very limited market. A kiln owned by a local magnate could expect orders from its owner. Some argue that the master potter was also able to sell freely to other buyers. Secondly, a financially strong owner was able to build the kiln in the first place - and had the right to do so, unlike common people. But perhaps the most important merit for the potter was recognition. This is certainly true in the case of Tōso.

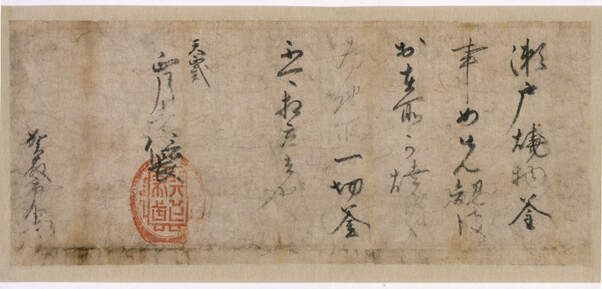

Nobunaga understood this latter point very well. This is why he issued the first kamajirushi, or potter’s marks, for the first time in Japan. He awarded them to six potters in Seto. “In my opinion it is a sign of Nobunaga’s genius that he in this way established a distinction between artisan (shokunin) and fine art potters (geijutsuka). This is the origin of the Living National Treasure potters and the Order of Cultural Merit for potters we have today,” Nishimura writes (1).

Nobunaga also saw the value in skill. He made Kagemitsu his protégé, and licenced him to build a kiln in Mino. Kagemitsu brought with him the competence to produce tea bowls today regarded as some of the finest classic styles in Japan.

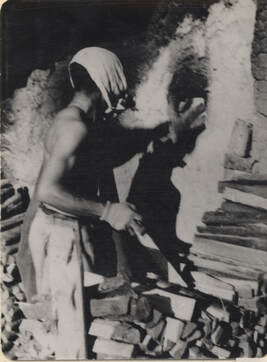

As mentioned above, in order to produce ceramics, a potter had to have permission, and this fact has played an important role throughout the history of ceramics in Japan. In the case of Kagemitsu, the kiln fell under the jurisdiction of Lord Tsumagi, who ruled over the area. The ruins of the Tsumagi Castle still linger on a mountain top overlooking the plain below. There, halfway up the steep hillside, lies a huge boulder with lines of holes on its surface. They are marks left by workers who had tried to cut the boulder into smaller pieces for the castle wall, but must have given up at some point. Had they succeeded in their task of carrying the huge stones up the mountain, they would have remained there until this day. The sight conveys an impression of how hard labourers were made to work for the ruling class at the time. I imagine that the workers at the kilns also had to endure hard labour in the humidity and heat of the summers, and the crisp cold days of winter. But pottery was what put rice on their tables (often mixed with millet, which was common in the mountainous regions).

The licence issued by Nobunaga states that Kagemitsu and his workforce may only work at the kiln the licence is issued for. They were not allowed to move the kiln to another location. This restriction would prove to be impractical. The kilns of those days consumed large amounts of firewood, and over time all the trees near the kiln would be cut down. But the licence would still prove its worth for generations to come. After Kagemitsu’s death it would be passed on from father to son for generations.

Nobunaga’s successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, continued the patronage of potters and tea masters. In particular, the tea master Sen no Rikyu set the tone for the tea ceremony and established a tradition that continues to this day. Hideyoshi died from illness on September 18, 1598. After a fierce war the Tokugawa shogunate was established on March 24,1603 in Edo (present day Tokyo), and the country was finally unified. The center of ceramic production began to move from Seto to Mino. Two generations down the line, Kagemasu, a grandchild of Kagemitsu, moved to Hirano in Tajimi in 1641. With Nobunaga’s licence in hand, he built a new kiln. His licence would be transferred from father to son until modern times. This was the dawn of a new era -lasting for two centuries- of peace and stability, when luxury tea utensils would become less important and production would start to meet the mass market demand for cheaper everyday goods.

Nobunaga’s successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, continued the patronage of potters and tea masters. In particular, the tea master Sen no Rikyu set the tone for the tea ceremony and established a tradition that continues to this day. Hideyoshi died from illness on September 18, 1598. After a fierce war the Tokugawa shogunate was established on March 24,1603 in Edo (present day Tokyo), and the country was finally unified. The center of ceramic production began to move from Seto to Mino. Two generations down the line, Kagemasu, a grandchild of Kagemitsu, moved to Hirano in Tajimi in 1641. With Nobunaga’s licence in hand, he built a new kiln. His licence would be transferred from father to son until modern times. This was the dawn of a new era -lasting for two centuries- of peace and stability, when luxury tea utensils would become less important and production would start to meet the mass market demand for cheaper everyday goods.

TōsO in the Edo era

The Mino Tōso, Kagemitsu, had now been gone for a long time, but still continued to have a presence in the daily life of potters in the region. By the middle of the 17th century, many new kilns had been established and competition intensified. This led the Tokugawa Bakufu -the military junta government in Edo- to prohibit new construction of kilns. It became vital for a potter to be able to assert his right as a ceramic producer. Both a wealth of documents and oral proof was necessary time after time, as the government kept introducing new kiln reforms. In this process, the line of descendants after Kagemitsu made good use of the name of their founding father, the Mino Tōso. If one could prove to be a descendant of Tōso one’s job was secured. It is apparent that Nobunaga’s name, too, still garnered great respect, as he was the issuer of the licence. Nobunaga had been a wartime ally with the first Shogun ruler in the new era - Tokugawa Ieyasu.

We see evidence -in historical records from the 1800s- of just how important Tōso’s name became, as the end of the Edo era was approaching. Across the creek behind our house here in Tajimi, lies the village of Takata, which is blessed with a kind of clay that is very well suited for the making of vessels for liquids. The properties of the clay are such that these vessels don’t leak. Takata tokkuri - sake flasks containing the popular rise wine - were sold very successfully in Edo - now a million city. At this time a man by the name of Toda Saburō made good money from brokering for a kiln in Takata, selling large quantities of sake to buyers in Edo.

By this time the Shogunate in Edo had begun weakening, and the kiln administrative system started to fall apart. With the system out of control, kilns started to pop up everywhere, as the market for mass-produced ceramics grew rapidly. Saburō was very troubled by this development - he could no longer monopolize the business. He therefore spent a large amount of money - 28 ryo - to have testimonies made proving his right to the business. He handed in a request to the authorities to stop any new kilns to be built along with these documents, but to little effect. Only a few years later, the administrative system was abolished in 1872 after the collapse of the Bakufu.

the modern era

With the Meiji Restoration in 1868 and the establishment of a new government, the market was liberalized and kilns grew rapidly in numbers. Trade associations began to be formed. The Mino Ceramic Industry Association was established in 1886 as the central organisation. The merchant class, while formally close to the bottom of society in the Confucian order maintained by the Bakufu, had been on the rise for a long time. Money, after all, is power. They now stepped in to back the establishment of new kilns by lending money for raw materials, daily necessities and so forth, which they deducted with interest from the income of the kilns.

Times changed again when Japan went to war with Russia. This caused a huge growth of exports, including ceramics. Surprisingly, the expansion also became a big headache for the ceramics industry in Tajimi, as the manufacturers saw a lost opportunity for better profits. The centre of the city had a large concentration of ceramic merchants, who acted as wholesalers for the kilns further out, such as those in the neighbouring Toki district. It seems the manufacturers must have increasingly seen them as unnecessary middlemen. If they could avoid paying the wholesalers, margins would grow significantly. Tajimi was a key point in the distribution net to other parts of the country. A new train station had just been opened, and was planned to greatly facilitate the traffic of goods. I suppose the merchants had already begun to freight their goods on the new line to the big city Nagoya nearby. The merchants in Tajimi formed an alliance and cancelled their contracts with the Toki district manufacturers.

Times changed again when Japan went to war with Russia. This caused a huge growth of exports, including ceramics. Surprisingly, the expansion also became a big headache for the ceramics industry in Tajimi, as the manufacturers saw a lost opportunity for better profits. The centre of the city had a large concentration of ceramic merchants, who acted as wholesalers for the kilns further out, such as those in the neighbouring Toki district. It seems the manufacturers must have increasingly seen them as unnecessary middlemen. If they could avoid paying the wholesalers, margins would grow significantly. Tajimi was a key point in the distribution net to other parts of the country. A new train station had just been opened, and was planned to greatly facilitate the traffic of goods. I suppose the merchants had already begun to freight their goods on the new line to the big city Nagoya nearby. The merchants in Tajimi formed an alliance and cancelled their contracts with the Toki district manufacturers.

Times were different in those days. As part of the city development, in spite of local protests, the administration built a red-light district -Nishigahara- in 1889. The patrons would obviously be the wealthy merchants in the centre of the city (2). In spite of some living a lavish life, however, tensions grew between the producers in Toki and the wholesalers in Tajimi. The alliance of merchants pledged never to buy from Toki again. To counter this, the producers opened a manufacturer alliance sales office in front of the new train station in order to bypass the wholesalers, from which they blocked sales to the city merchants. All this threatened to stop all trading, and related businesses such as firewood stores were forced to close. The red-light districts in Tajimi were among those hardest hit. Tajimi hosted the largest such district in the Tōnō area.

Finally, Kato Suezaburō, a ceramics dealer, was able to intervene and settle the dispute. And now again, Tōso steps out of the shadows. As a token of the peace brokered between the two camps, monuments commemorating Tōso were erected in Hirano Tajimi.

Even to this day, the ceramic unions in each district are holding a Tōso festival in front of the monuments every year. In June 1901, a train carrying a huge stone from Sendai arrived at the newly opened train station. It was loaded on a trolley and many people pulled the ropes attached to it. They hauled it up the steep slope to Hirano Park, where this Mino Tōso Monument now stands. The best artists in Japan, a stone mason, a scholar of Chinese, and a calligrapher collaborated to create the inscription on the monument.

Finally, Kato Suezaburō, a ceramics dealer, was able to intervene and settle the dispute. And now again, Tōso steps out of the shadows. As a token of the peace brokered between the two camps, monuments commemorating Tōso were erected in Hirano Tajimi.

Even to this day, the ceramic unions in each district are holding a Tōso festival in front of the monuments every year. In June 1901, a train carrying a huge stone from Sendai arrived at the newly opened train station. It was loaded on a trolley and many people pulled the ropes attached to it. They hauled it up the steep slope to Hirano Park, where this Mino Tōso Monument now stands. The best artists in Japan, a stone mason, a scholar of Chinese, and a calligrapher collaborated to create the inscription on the monument.

In October 1901 the Mino Ceramics Association was established, and Nishiura Enji, one of the Japanese porcelain masters, was appointed deputy union president.

Three years later on November 30, 1906, the inauguration ceremony of the Tajimi Mino Tōso Monument was held with great pomp. There was a great festive mood, rice cakes, fireworks, and dancing geisha. The park was lit by electric lights, as electric power had recently been installed in the town. People must have looked at this sight in awe.

The spirit of Tōso lives on. His style of pottery saw a strong revival of interest in the early Showa period that has expanded to an international audience. Every year his name is celebrated at his monument. A great ceramic festival was instituted as an extension of those celebrations. Today it draws tens of thousands of people from all over the country. And all of this, because one powerful man signed a paper and gave it to a particularly gifted potter, so he could open his kiln here in the Mino region.

But there is still a mystery to solve. Many discoveries have been made about the history of Mino ware after the institution of Kagemitsu as the Mino Tōso. Was he really the greatest pioneer, or even the first of his kind? Or is he the one that happens to remain in the historical records? We know that there were others in Mino, long before Kagemitsu, who were influenced by the wabi-sabi philosophy first introduced as an element of the tea ceremony. This was precisely the style the samurai admired so much. We know that some of them here in Tajimi produced Shiro tenmoku (white tenmoku), a crown jewel among such fine pottery. Were the Meiji era merchants and manufacturers mistaken to name Kagemitsu their Tōso? Is he a spirit still remaining in the shadows?

Perhaps, if he is, and one day decides to step out, we shall find out.

But there is still a mystery to solve. Many discoveries have been made about the history of Mino ware after the institution of Kagemitsu as the Mino Tōso. Was he really the greatest pioneer, or even the first of his kind? Or is he the one that happens to remain in the historical records? We know that there were others in Mino, long before Kagemitsu, who were influenced by the wabi-sabi philosophy first introduced as an element of the tea ceremony. This was precisely the style the samurai admired so much. We know that some of them here in Tajimi produced Shiro tenmoku (white tenmoku), a crown jewel among such fine pottery. Were the Meiji era merchants and manufacturers mistaken to name Kagemitsu their Tōso? Is he a spirit still remaining in the shadows?

Perhaps, if he is, and one day decides to step out, we shall find out.

notes

- Article: Katsuya Nishimura, 桃山茶陶の格別の美しさの秘密 (“The Secret behind the Beauty of Momoyama Tea Bowls”). Scroll back to text

- After a rocky start because of the recessions in the beginning of the century, business was flourishing in Tajimi’s red-light district by the mid 1920s. Around one hundred prostitutes were active at the peak of its existence. If life in the geisha district was anything like other parts of Japan, it must have seen many dramas play out, both between lovers, and those in marriages caught in a love triangle. There must have been wealthy clients and patrons, as well as less wealthy ones, asking for credit from geisha house owners, or unable to pay. Stories I have heard, but cannot reveal, provide a strong hint in that direction. The red-light district was shut down in 1958 after the introduction of new anti-prostitution laws. Scroll back to text

more history articles on mino ware

Six essays for the pottery lover.